Merging descriptive metadata sources with OpenRefine, Python, and MySQL

I recently had a chance to work with a collection at BAMPFA that I find really fascinating and that is definitely under-utilized (and also basically undiscoverable at the moment). We have a collection of audio recordings going back to the 1970s that is described in disparate data sources including a paper card catalog (fuck yeah!) and I took a deep dive into merging and normalizing these sources. Here’s the Github repo that includes the scripts and data sets I used.

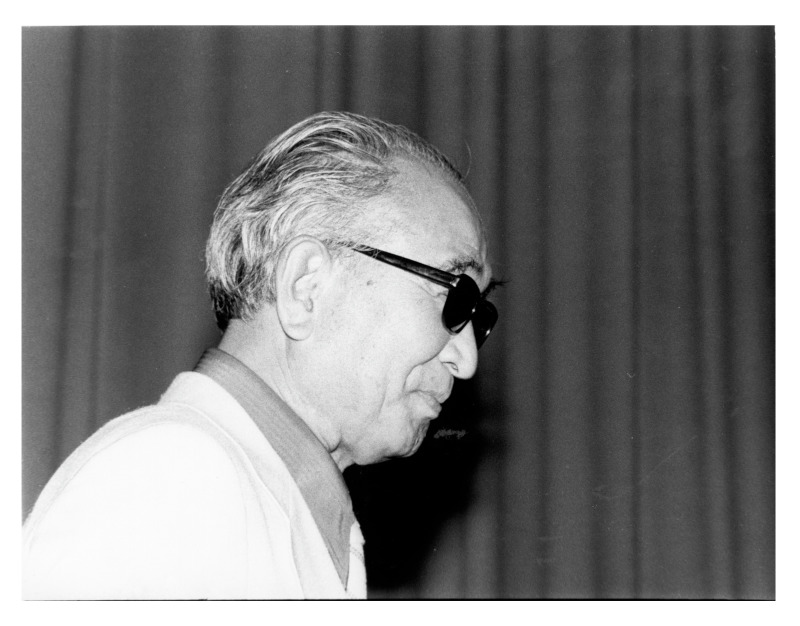

Here is Akira Kurosawa chilling at the PFA. Image courtesy Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive.

Here is Akira Kurosawa chilling at the PFA. Image courtesy Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive.

Since about the mid-1970s (we have some earlier recordings, but it was inconsistent then), the Pacific Film Archive has been recording guest speakers related to its acclaimed film programming. These have mostly included filmmakers and film critics from around the world, but there are outliers like the one time Angela Davis was hanging out with Ousmane Sembène in 1978. The early years in particular are extremely dense with top names of international and experimental cinema–Chantal Akerman, Werner Herzog, Jean-Pierre Gorin, Richard Serra, Yvonne Rainer, the Kuchar brothers were just some of the frequent guests of the late 70s. There were also visits from Soviet cinema leaders and members of the “Third Cinema” movement, among many others, along with deep dives into historical Hollywood genre pictures and classics (remember when King Vidor and Doug Sirk dropped by?).

Until 2006, these recordings were made on consumer-grade audio cassettes, along with a handful of reel-to-reel tapes, which clearly does not bode well for their long-term accessibility to film scholars and nerds. We have been digitizing tapes piecemeal with greater or lesser success in-house, and in partnership with projects like California Revealed. This fall, we applied for and received a grant through the Council on Library and Information Resources to digitize 750 of the earliest recordings.

A key element of this digitization project will be to align the existing descriptive metadata about the recordings with the digitized assets that we’ll get from our vendor. I’m going to describe my efforts to clean the existing data about these recordings and merge it with descriptive data related to our born-digital audio recordings.

analog-4-evr

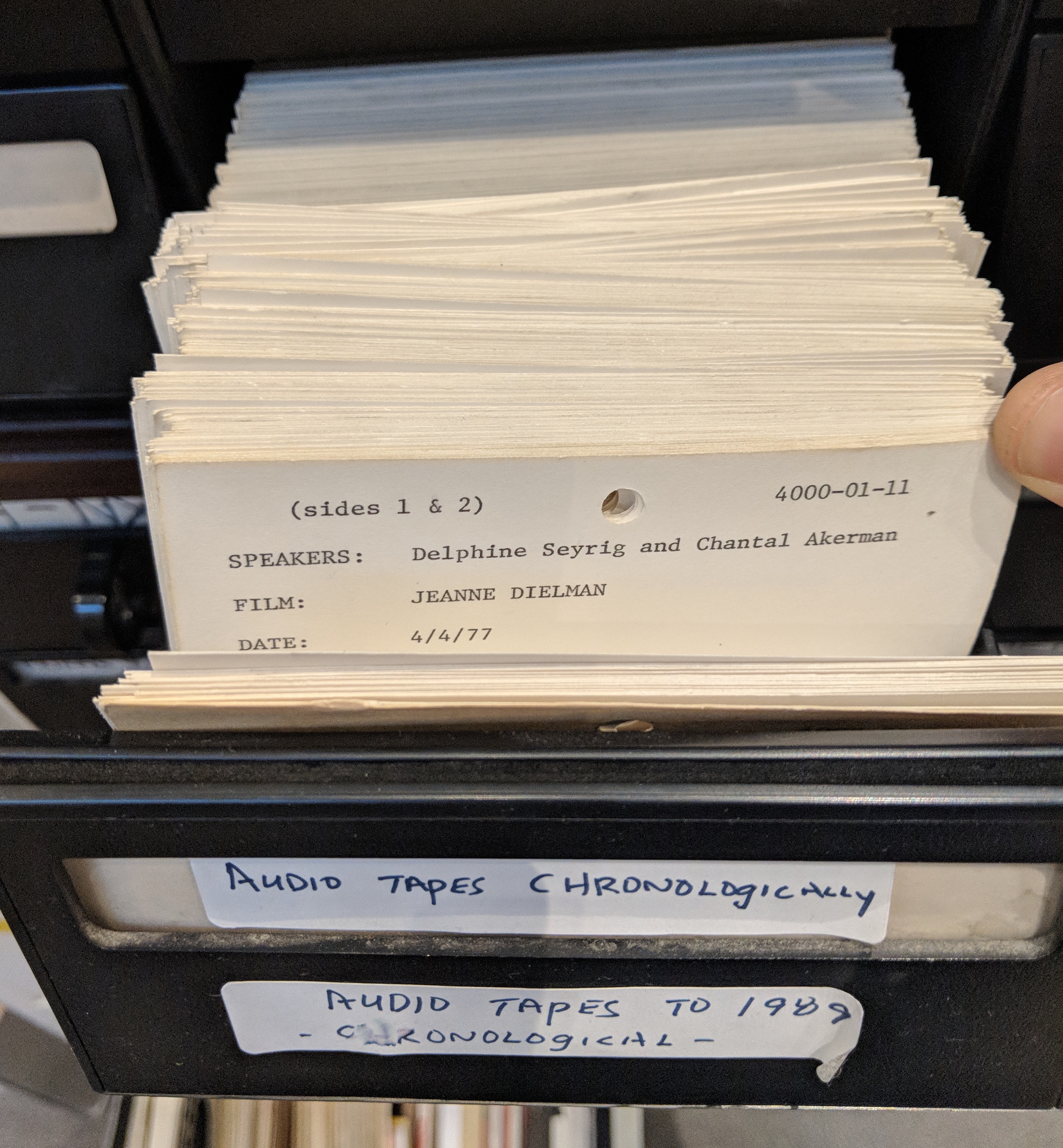

Until some unknown time in the early 90s, there was a paper card catalog kept by whoever was responsible for keeping the tapes in a closet somewhere:

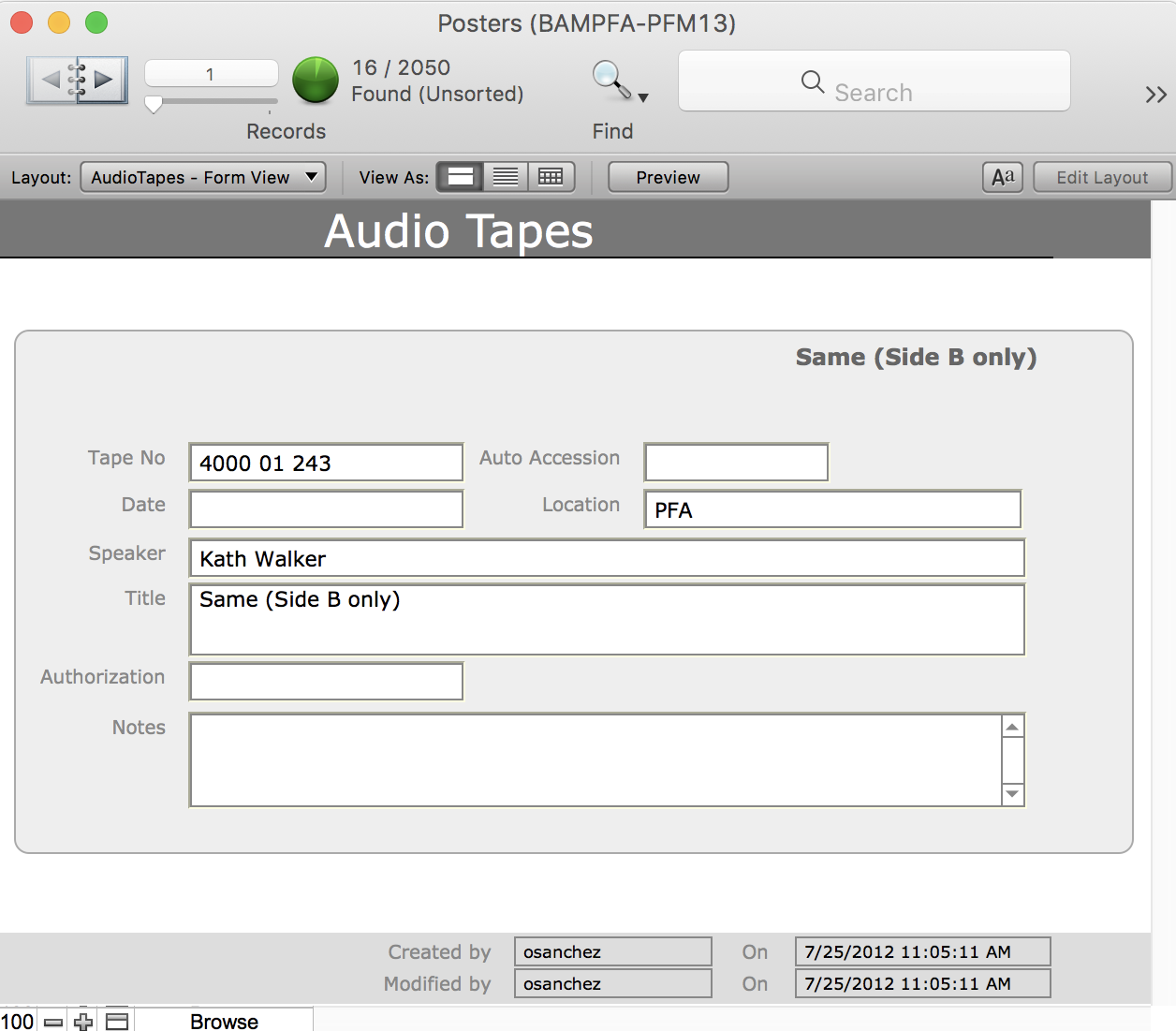

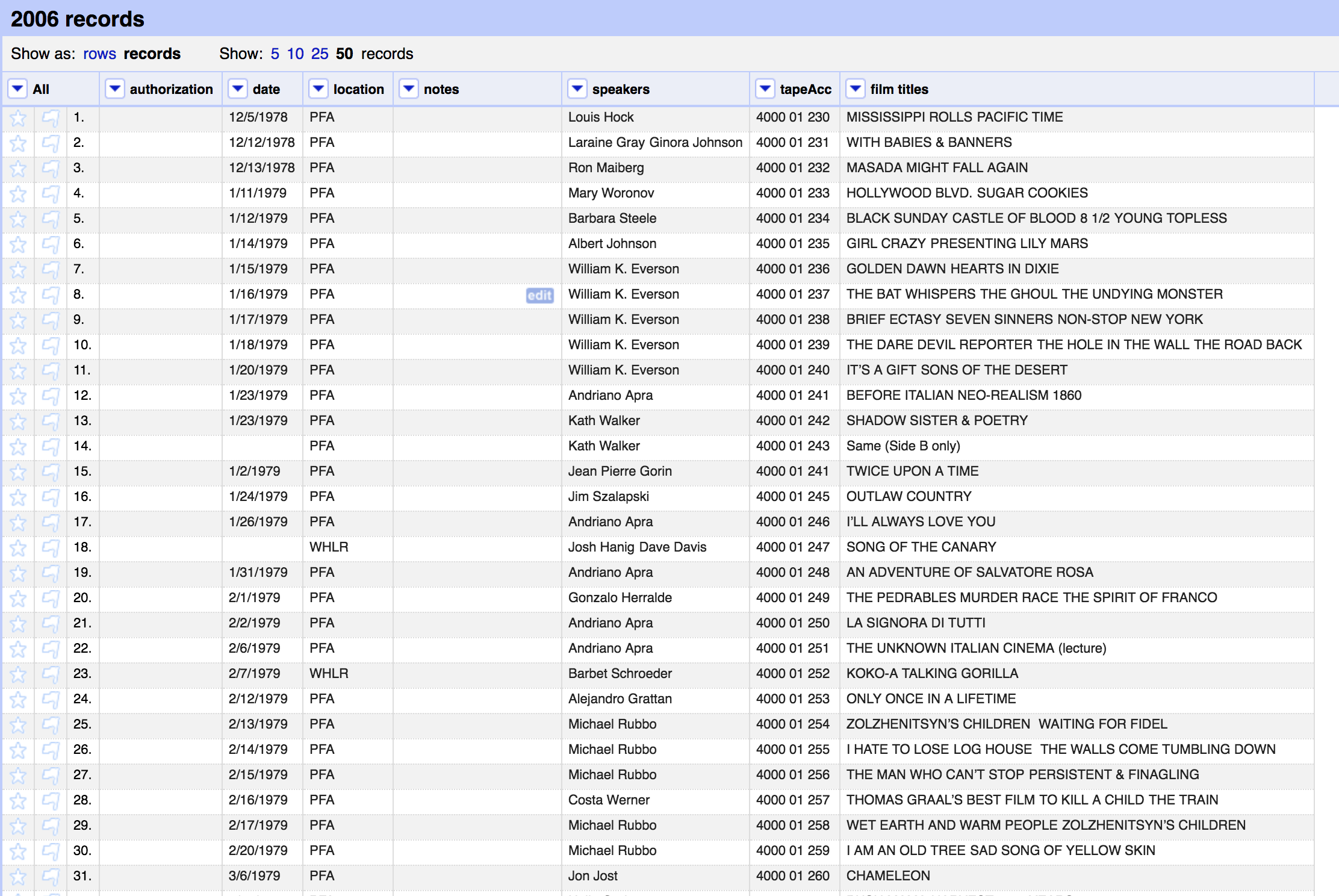

Somewhere in that distant past, the PFA film library was given control over the tape collection and someone made a database for basic information about the recordings that was on the cards (the tapes were also transferred to our film vault some time in the 90s…). That data was updated with each new recording until PFA stopped using cassettes. In 2012-ish the database was merged with a FileMaker database describing our poster collection (no one seems to know why). The basic information recorded included Speakers, Film titles being discussed/shown, date, notes, and any information about release forms signed by speakers:

take a good sniff of that data

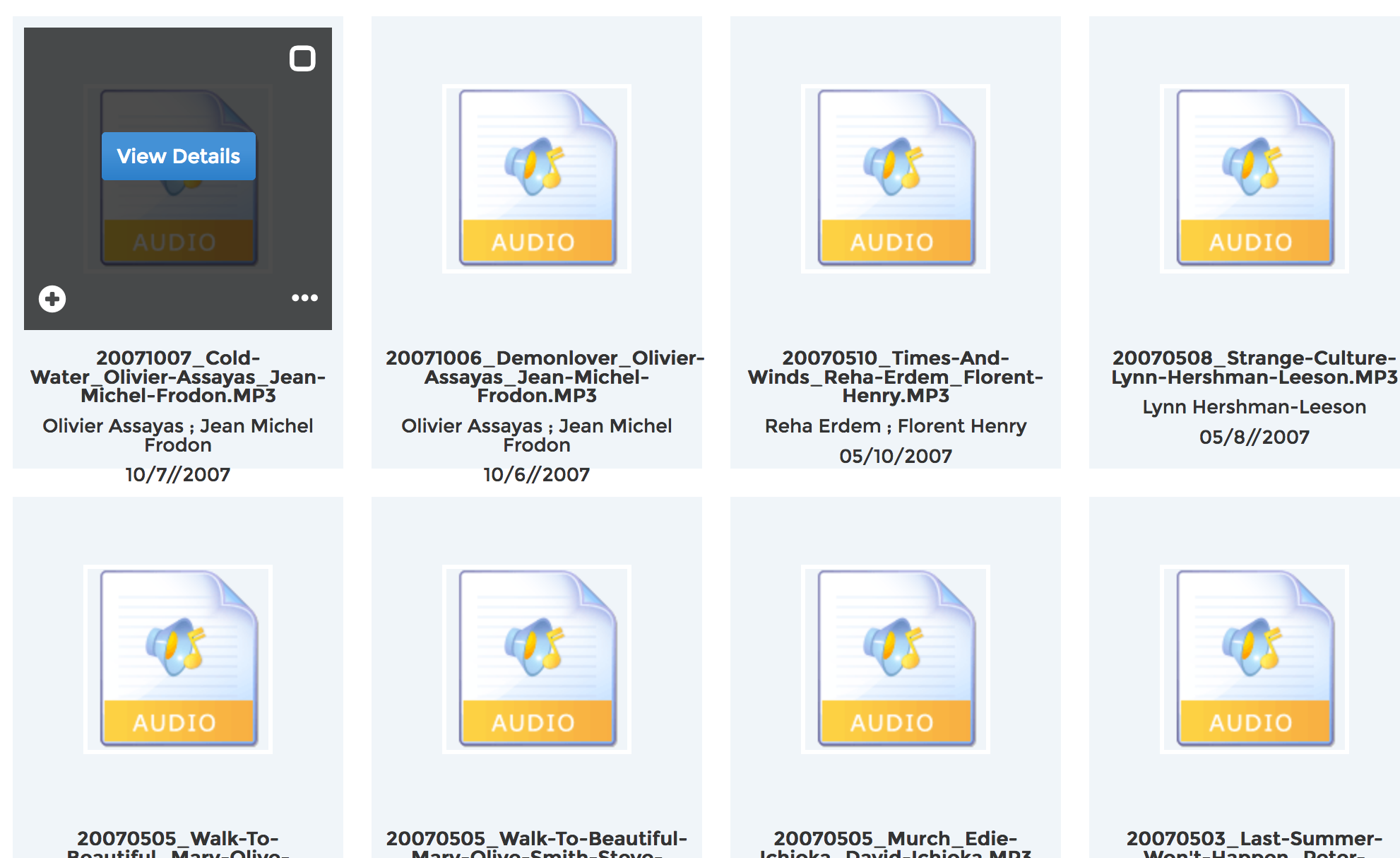

Between 2006 and 2015, the born-digital audio recordings had no metadata recorded other than what was in the (helpfully very descriptive and quite consistent) filename. When we adopted a new digital asset management system in 2015, I wrote some sed commands to parse all these filenames and extract things like dates, film titles, and speaker names based on positional delimiters. The parsed data was imported as a CSV and added to records for the existing assets. It was far from perfect, and it was much less rich than the database information, but it was better than nothing. Slowly, staff and student workers have added data like additional film titles and release form status.

there are still errors from the original filename parsing :(

“OpenRefine is magic”

The CLIR digitization project seemed like an excellent time to clean up our existing data game and also merge our data sources into a single stream that can be updated both as new born-digital recordings are added and as tapes get digitized. The only problem is that the data from FileMaker and Piction had different “shapes!” Aside from having different descriptive fields, they also recorded things like repeating/multiple values differently. For example, in FileMaker, multiple values in a single field were separated by newlines, but in Piction, multiple speaker names and film titles are separated by semicolons (;). The basic domain of the data is the same in both cases, though and the task seemed doable.

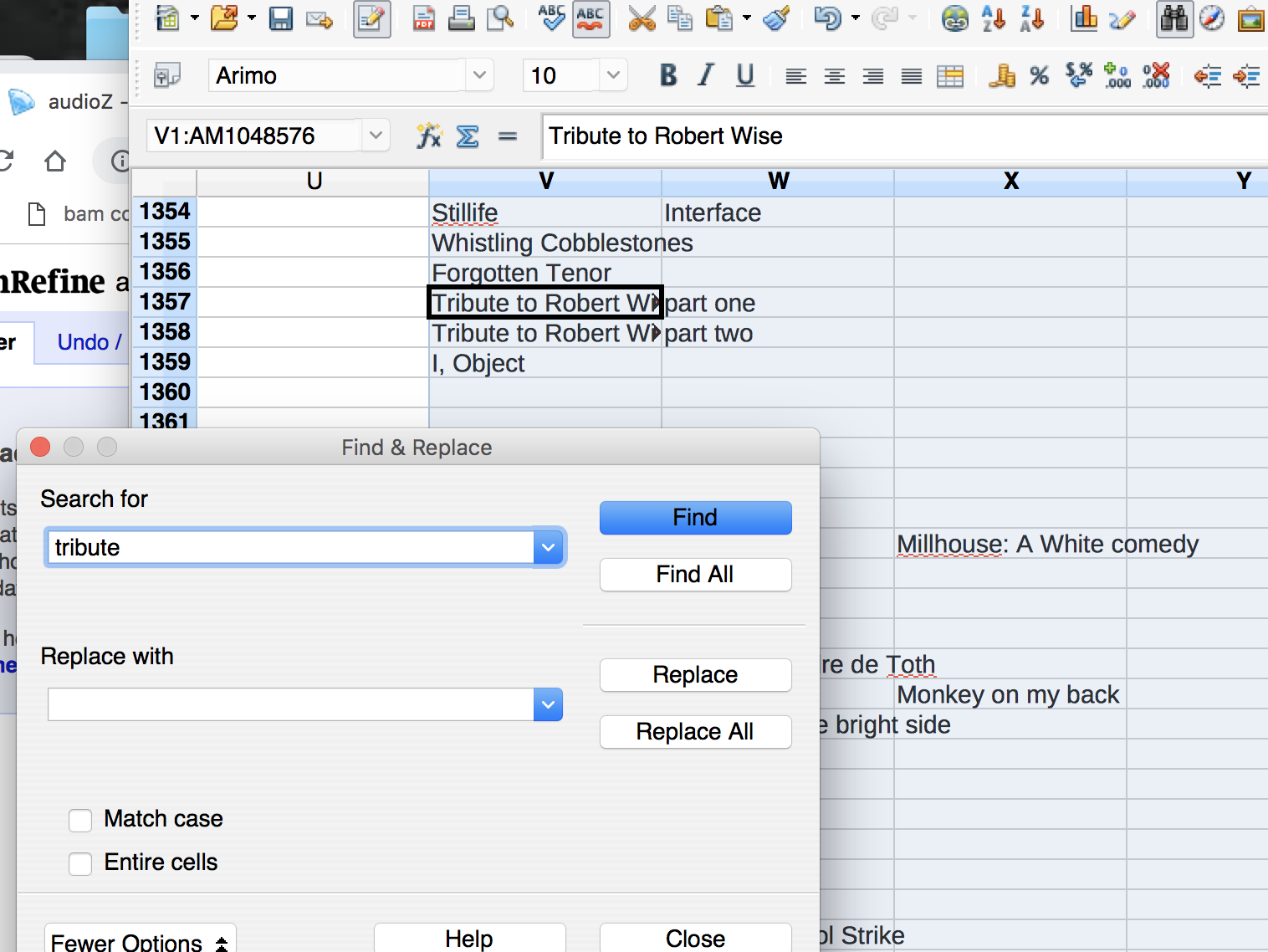

OpenRefine was a natural choice as a tool both to clean up the two data sources and to facilitate normalizing the data. I would also need to use OpenOffice to do things like moving columns around more easily, searching for keywords across columns, and doing global search and replaces. The end result will be a new database to serve as an authoritative data source/collection management system for this collection (for various reasons–institutional, political, maybe technical–we can’t merge the data into our CMS for the film collection or the CMS for our art collection). This data source will also provide descriptive metadata to our new in-house digital preservation system, EDITH.

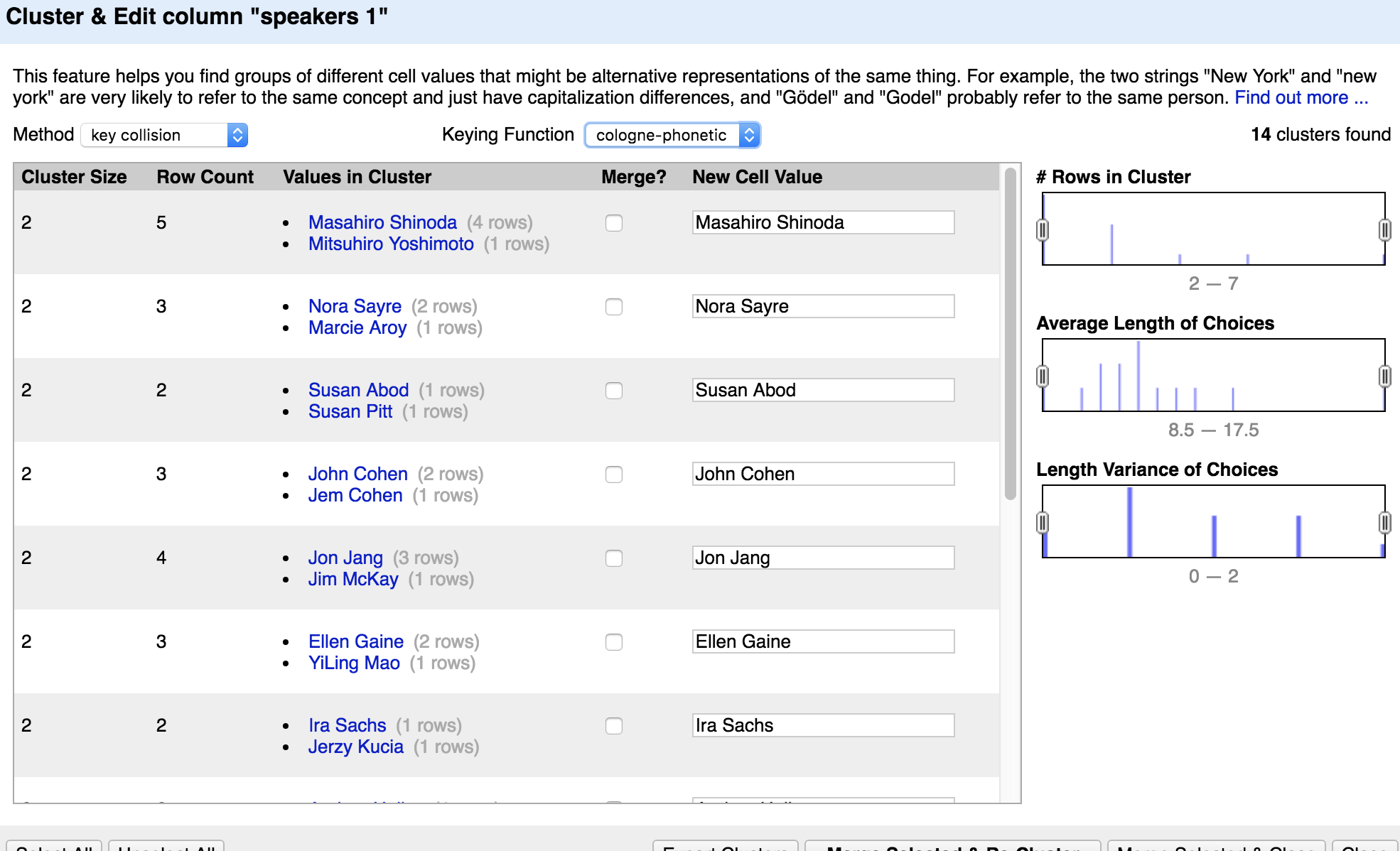

Once the data was exported as a CSV from both Piction and FileMaker, I created a project for each data set in OpenRefine, which I edited independently before merging. In these CSV files (basically a spreadsheet), each row represented a record for a recording, and each column represented a field of data. OpenRefine includes built-in tools to do things like parse a column of data and split it into new columns based on a separator in cell values (or really you could design lots of other conditions by which to parse column data…). It also includes tools to search for potential matches in slightly differing values across cells. For example “chantal akerman” and “Chantal Ackerman” almost certainly refer to the same person, and OpenRefine has a function called “clustering” that is fantastic at finding these matches. There are several different algorithms you can use to identify matches, and several of them are adjustable in their “hunger” to find a match. I won’t pretend to understand the math behind these algorithms, but they generally have to do with a computed “distance” between two strings. The algorithms differ in how they compute distances and you can use each of them to find matches that other algorithms miss (the really insane ones are the “phonetic” matches… dark magic for sure).

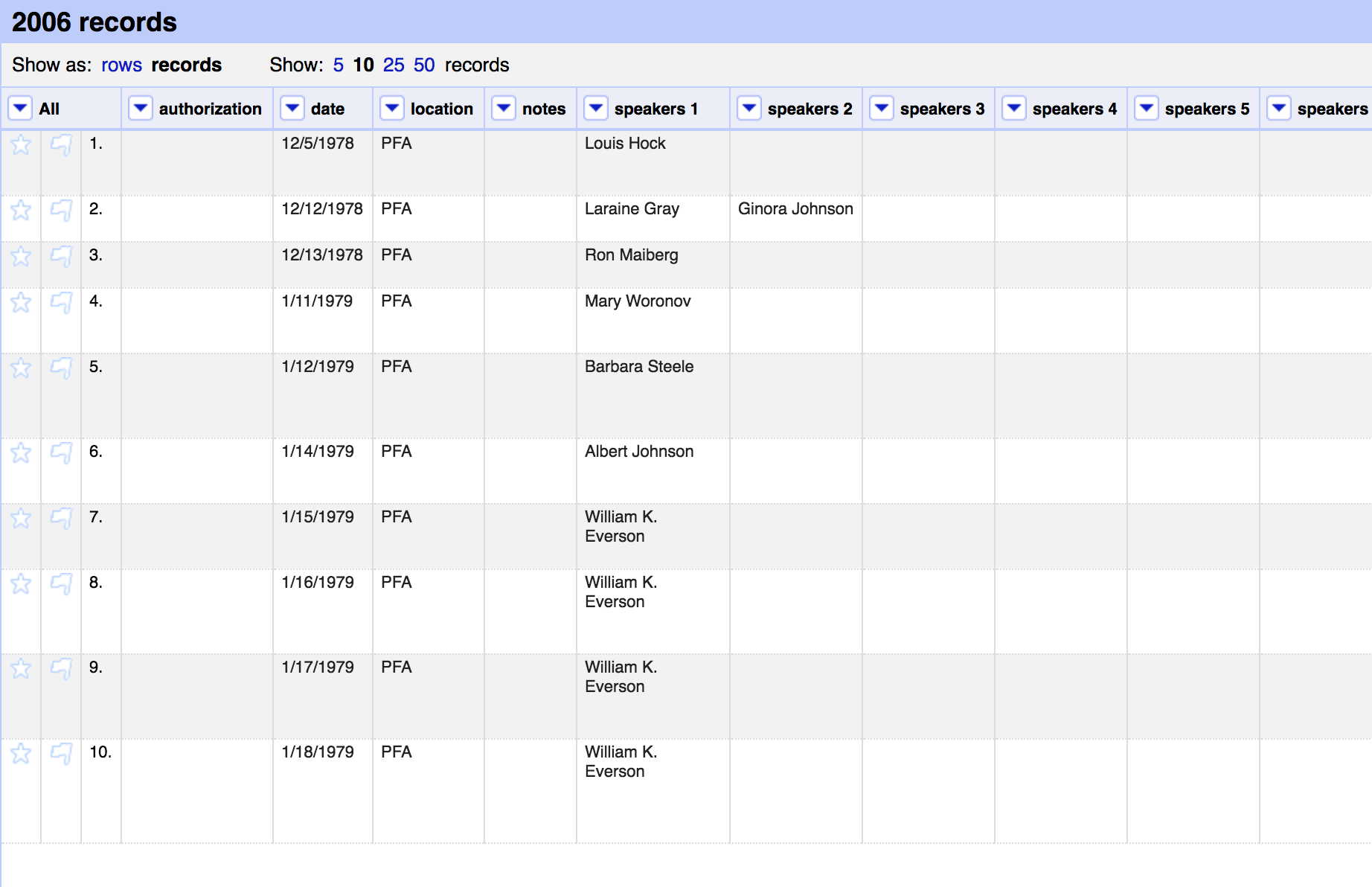

The first steps were to split apart cells that contained multiple Speaker and Film title values. This was pretty straightforward for most of the records, since the delimiters were pretty consistent. The end result for both speakers and film titles was a set of columns with each cell containing (ideally) a single name or title. For the FileMaker data, for example I wound up with 12 Speaker columns and 18 for Film titles.

Check it out:

before

after

… now to clean up the split column values

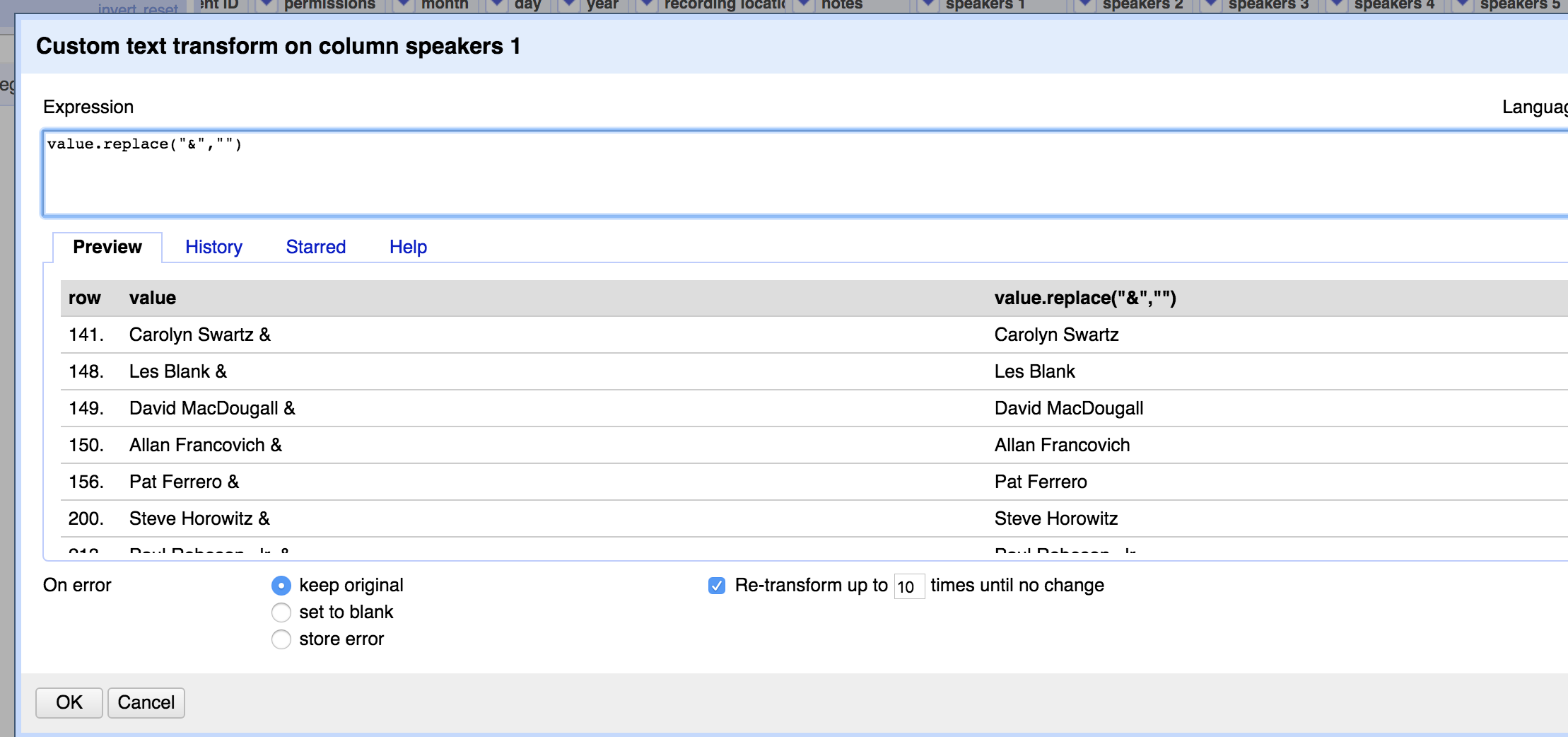

There were a lot of cases, though, where multiple values were joined with text like “and”, an ampersand (&), or just a comma. Luckily, once the “normal” cases were out of the way, I was able to do a simple text filter on the original column to separate out the values with outlier delimiters.

Next came the really fun part of using Cluster & Edit to merge values that were entered slightly differently in the data sources. The example below shows that OpenRefine knows there’s a direct link between GIRL CRAZY and GUN CRAZY… :(.

Now the data was ready for human-intensive and fairly tedious manual corrections. First, I had to filter out things in the film title columns that were not really film titles, but “event titles” (like “Women of Color Film Festival” or “Eisner Awards”) or notes about the recording (“recording on side A only”).

looking for keywords across columns in OpenOffice

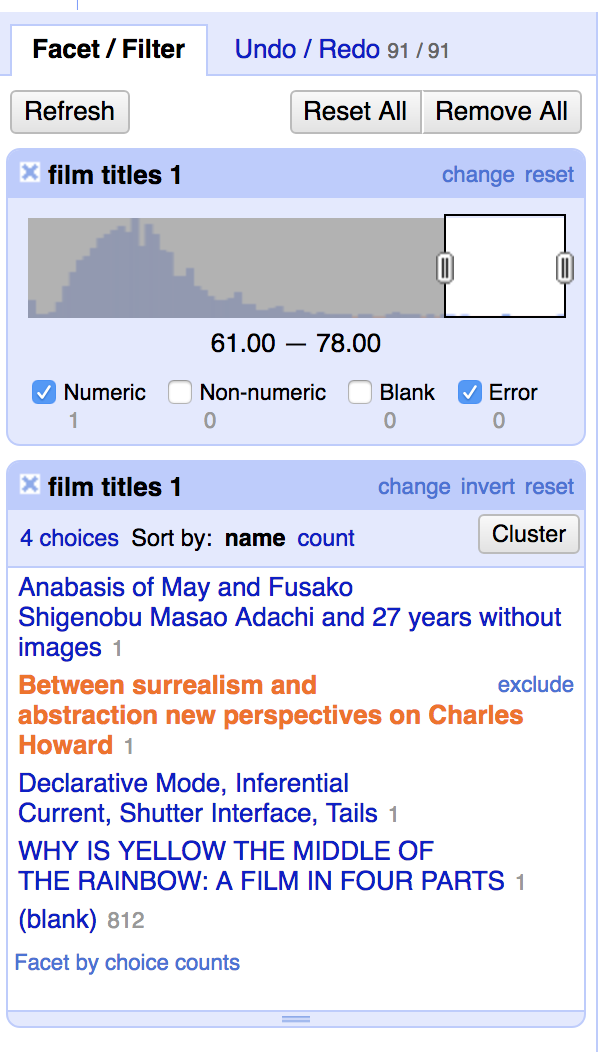

I wound up with a list of about 20 keywords that I used to filter these values and move them into more appropriate columns. The Piction data also included some event titles that weren’t easily filterable by keywords, but I was able to use text length facet to plot and identify incorrect “film titles” that were actually lecture titles:

Between Surrealism and abstraction: new perspectives on Charles Howard

Once the FileMaker and Piction data sets were cleaned, I added columns to each as appropriate so that the data would line up when I merged them (a.k.a. copy and pasted on spreadsheet under the other in Open Office).

PYTHON AKTION

Next came the fun part of using Python to parse the cleaned data and create a normalized view in which things like Speakers and Film titles are treated as entities alongside the “base” entity, which is the recording. I won’t go into the mechanics of each script, which you can find in the Github repository linked above, but I’ll try to describe the high-level data modifications.

The first script, audioNormalizer.py, read the combined CSV file and did the actual work of splitting each row in the CSV. It also created a JSON object with three sub-objects, one for recordings, one for speakers, and one for film titles. Each row in the CSV was put into the recordings object along with a unique identifier (0001,0002,0003, etc.), and each unique instance of a speaker or film title was added to its respective object, with a unique ID created for each. These IDs were then added to a list in the recording object.

Next, I used a script (audioDbBuilder.py) to construct a MySQL database that will hold all the data. In order to represent the relationships between, for example, speakers and recordings, I created “join” tables that represent these “many-to-many” relationships. For every time a speaker and recording are related, the join table has a row containing the unique ID for the recording and the speaker. This is the heart of a relational database in which data is only stored once rather than, for example, writing out “Mulholland Drive” in every recording record in which that film is discussed.

The last script (audioDataParser.py) reads the JSON object that was created in the first step and does the dirty work of making SQL statements to insert all the data into the database.

Next steps

It still is not 100% clear what we will do with the data beyond the scope of the CLIR project, but the goal is to have a database on our local network that we can use as a collection management system for all of our event-based audio recordings (we have a handful of officially accessioned audio works in our collection, but BAMPFA does not routinely collect things like music, sound art, etc.). The simplest option will be to use the MySQL output of this project and recreate it in FileMaker, which is in heavy use at BAMPFA and is already in place on our network. Though I’m not a huge fan of FileMaker, our staff is used to it and it would be easy to transition into making records for new recordings in this database. It will also be easy to use such a database in our digital preservation workflows as a source of descriptive metadata to store with Archival Information Packages.

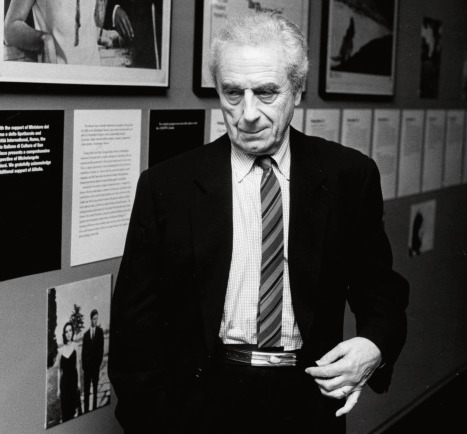

gratuitous picture of Michelangelo Antonioni looking cool at the PFA in 1993. Photo courtesy BAMPFA.

In the immediate future, we will provide the metadata to the digitization vendor for our CLIR project. One of the goals of that will be for the vendor to return MARC XML for us to batch load into the UC Berkeley library catalog. I’m… less than convinced we will get usable MARC XML right off the bat, so another project will be to make sure that things like speakers get into 700 fields as appropriate/applicable. More hopefully, we will be able to add descriptive metadata to archive.org records for the streaming files.

I’d love any feedback about the project, the data, or any other thoughts! Get in touch by email, on Github, or Twitter!