DIY open source digital preservation 4 n00bz: Ethics and code joy

This is the long, rambling, basically unedited text of a presentation I gave at the 2018 Association of Moving Image Archivists annual conference in Portland. The panel was shared with Susan Barrett, who discussed ways to secure buy-in from administrators and other important stakeholders when proposing open source projects. Our panel was part of the Open Source Toolkit stream at the conference. You can find the slides here. Also the panel was live streamed and recorded.

source: http://urbanbushbabes.com/a-behind-the-scenes-look-at-the-preview-diy-or-die-exhibit

source: http://urbanbushbabes.com/a-behind-the-scenes-look-at-the-preview-diy-or-die-exhibit

Hello my name is Michael Campos-Quinn and I’m the Metadata and Digital Asset Manager for the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. That basically means that I am a cataloger and also responsible for the day to day care of digital assets that include still images and digitized A/V material in the museum and the film archive. I am also involved in digitization project planning, in particular where projects impact metadata, storage, and access. Over the last year or so I have also become intimately involved in our digital preservation planning for digitized AV material. This last year of rethinking our approach to digital preservation has taken us down a really exciting path towards using and probably more excitingly, contributing to and creating open source tools.

This presentation is going to give some context for the decisions that we have made along this path, some of the rationales (and rationalizations) that have led us away from a set of proprietary tools and towards modular, open source ones, and hopefully also offer an assessment of our state of care, or our capacity for care, as a cultural heritage institution responsible for digital objects.

I also hope to present a subjective experience of what it has been like for me as a novice coder to build my skills in various programming languages, to learn about software development best practices, and also offer some reflections on what has brought me here: my gender, my particular position in my career, the institutional support I have and have not found, etc.

IT’S FOSS

Let’s briefly set some common ground for this discussion. The Society of American archivists (a good enough authority, I guess) defines open source software like this:

[Free and] Open Source Software

n. ~ Computer code that is developed and refined through public collaboration and distributed without charge but with the requirement that modifications must be distributed at no charge to promote further development.

source: https://www2.archivists.org/glossary/terms/o/open-source-software

What I take from this kind of definition of open source is the emphasis on tools being available for a community to use, tinker with, improve on, and re-share with others for the benefit of the community as a whole. This is often in opposition software development that is driven by a profit motive to create a monolithic “black box” tool to be sold as a product or as a service. That’s not to say that people don’t use open source software to make a profit, but that the tools are used and modified in the open as a matter of principle.

There are many, many great open source tools available to the AV archiving community, with some big names including FFmpeg and MediaInfo. Open licenses constitute another facet of what makes a project “open source” and some big players here are the family of Creative Commons licenses as well as software-specific licenses like BSD and GNU. These licenses provide language that spells out the community spirit in legally-binding form.

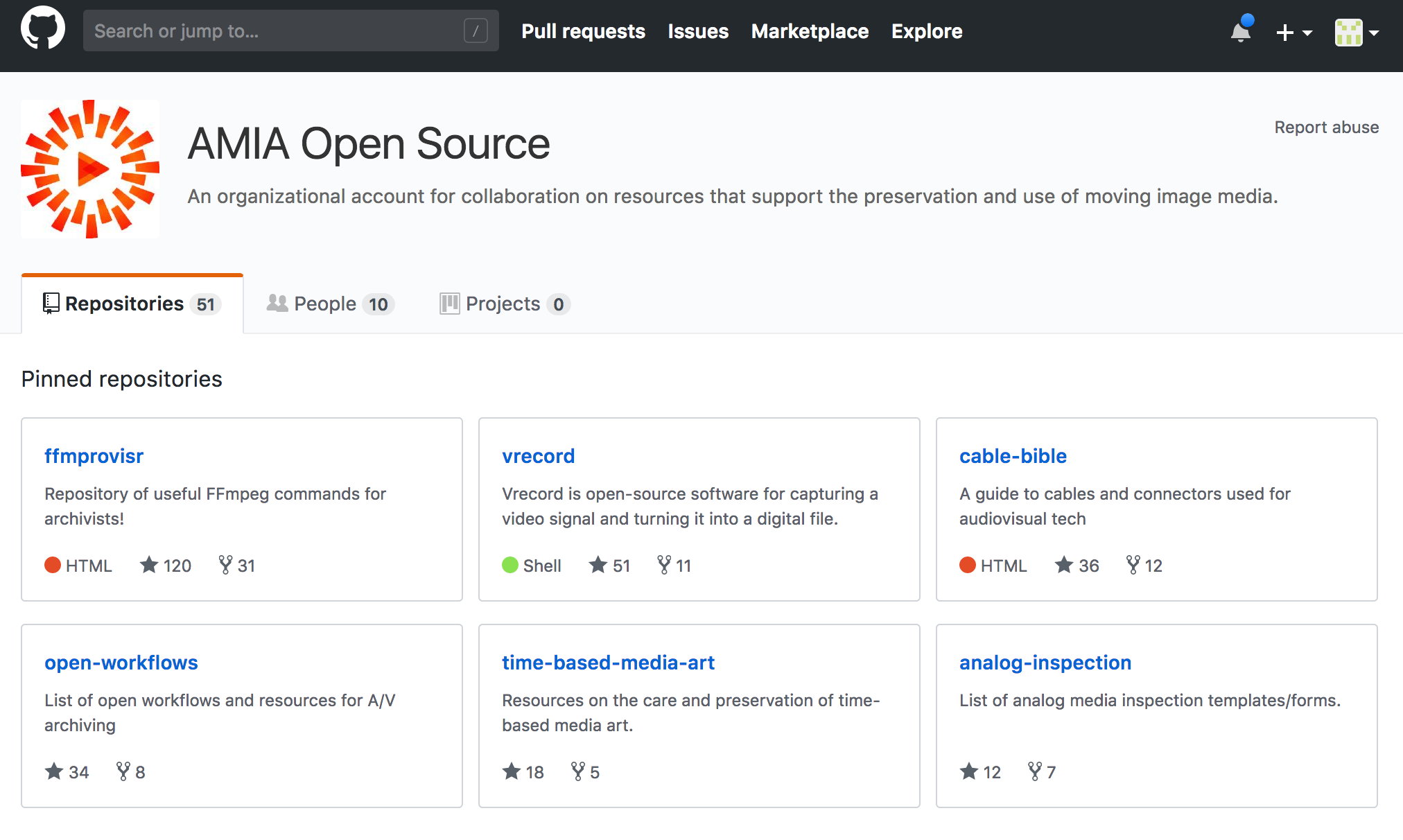

We’re really lucky that there are a lot of people involved with AMIA who actively contribute to tools like FFMpeg and MediaInfo, and that there is an active community within AMIA who are super smart and dedicated to creating new tools, new applications for existing ones, and also creating documentation that helps lower the barrier to connecting with and using some of these tools.

http://github.com/amiaopensource

http://github.com/amiaopensource

Again, the emphasis in this approach to software is sharing knowledge, working transparently, and contributing to the collective body of understanding. I keep using the word community, but really I think we’re a bunch of pinko utopianists.

Another excellent feature of the current state of open source software development is that with some skillful Googling and forums like StackOverflow, and a lot of patience and perseverance, you can teach yourself a lot of coding skills. On the other end of those Google searches are many, many people who are willing to share their knowledge and experience with you, so you can say that community begets community. And another shout out to the AMIA community, we’re lucky to be affiliated with a supportive contingent of individuals who are principled, generous with their time, willing to help out newbies, and have put years worth of effort into projects that are open for anyone to try out and add to on GitHub.

So I’ve built up open source as a community-driven counterpart to the tech-world ideal of capitalist entrepreneurs, and also as kind of “the right thing to do” when selecting a given software tool. There’s a flip side to that argument that I will get into a bit later, that also involves ethics. Our first obligation as archivists is to the collections that we steward. That also involves making sure that the technical and staff infrastructure are supported in a way that ensures continuity of care for our collections. Adopting open source tools is awesome, but jumping into a community pool means getting wet with all the other people who are in there.

Are you ready to join the Great [Open Source] Link?

It means taking responsibility for your contributions to the community and also internally supporting staff who build institutional knowledge of how a given set of tools fit into your workflows. In other words Free and Open Source software doesn’t come without costs.

Digital Preservation at BAMPFA

BAMPFA has been using a variety of approaches to digitization and digital preservation of AV material since the mid-2000s. Since then we have done in-house digitization of analog tape and film, in addition to outsourcing digitization on a project-by-project basis. Also, FYI, we continue to work on photochemical preservation projects.

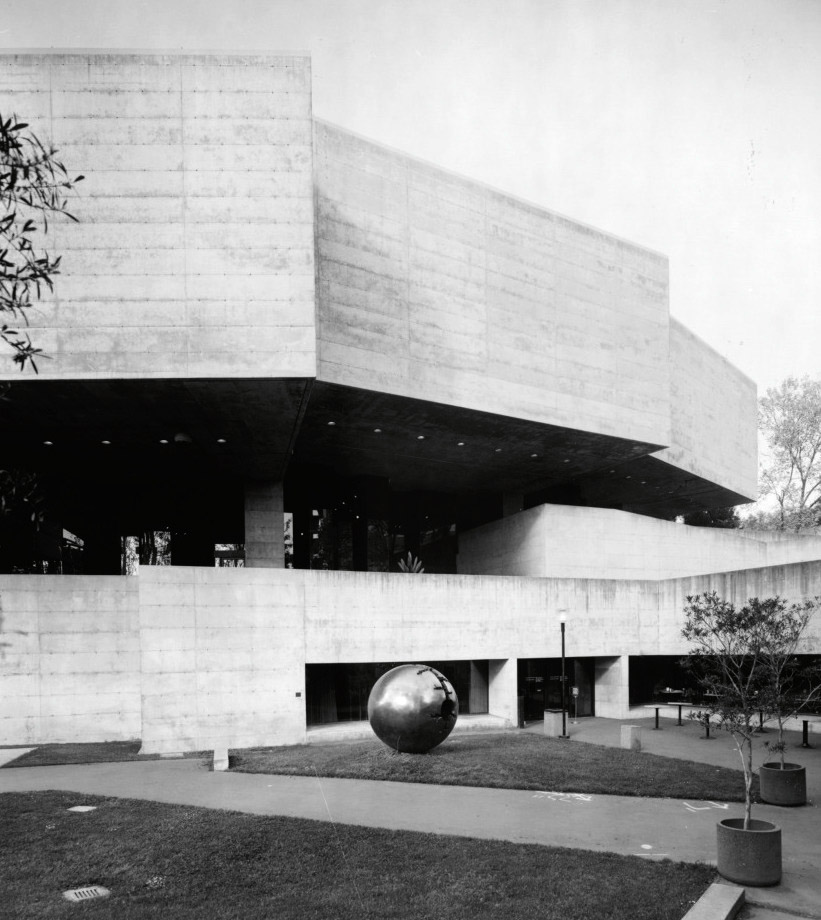

In 2016 we moved from our classic, brutalist all concrete building that opened in 1970

courtesy BAMPFA

to a more seismically sound one, and this move became an opportunity to rethink some of our infrastructure. This included setting up a network and various hardware that would support film and video digitization, centered around an NEH grant that was used to purchase a LaserGraphics film scanner.

Here’s where things get a little weird. For reasons that are unknown to me it became the responsibility of the contractor hired to install and configure our theaters, displays, and the internal A/V network to select and implement systems that would support digital preservation, storage, and access for our collections:

- Ingest preservation masters with descriptive metadata

- Store redundant master copies on LTO

- Make derivatives available

Our film collection curator and my supervisor in the library laid out the basic structure and technical requirements of such a system but for various reasons were not given much say in its selection or installation.

This basic structure spelled out that we would store redundant copies of our master files on LTO tape and that derivatives should be readily available for research. Descriptive metadata should be drawn from the film collection management system (a FileMaker database).

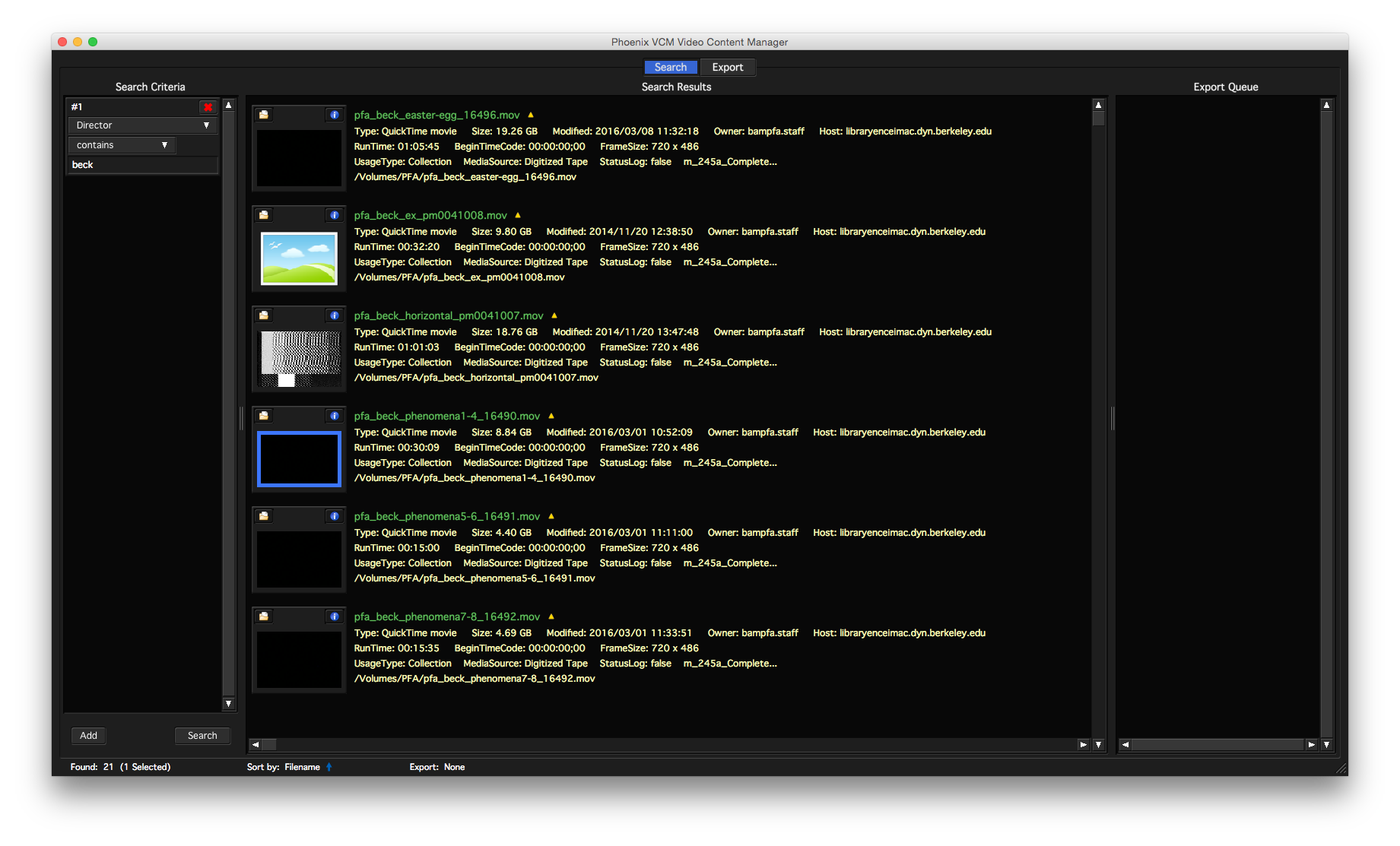

https://www.soleratec.com/solutions/law-enforcement/

The result was a contract for a proprietary system called Phoenix that was created by a company (Soleratec) specializing in tools to manage footage from police body cameras and dash cameras, security cameras, and apparently also sports production. To be fair, we never quite got Phoenix running in a production capacity, partly due to the subcontractor who was hired. But even if we had gotten Phoenix all the way up, we would have been stuck with an opaque proprietary system with a litany of complaints even beyond its less than modern user interface. Not to mention the questionable business interests of the company behind the product we were using.

The Phoenix user interface. Compare this to the inset in the previous image from Soleratec's Law Enforcement marketing.

As an arts organization whose collections are more often than not positioned against figures of authority and capitalism generally it seems like a betrayal of our institutional ethics to pay money to a company that exploits a market for “evidence management” for police and prosecutors, not to mention its branded body cameras and squad car cameras. There are also claims in SoleraTec’s marketing material about “automated metadata generation” and “smart redaction” that make my librarian hackles go up, and I have to wonder how successful public requests for evidence in such a system will prove to be.

Phoenix uses a proprietary database system that apparently was baked in place in the 90s when Phoenix was first developed. This made extending and accessing its metadata functions very difficult, which meant that our assistant film archivist had to copy and paste metadata by hand from the collection database. The other major red flag was that it uses a proprietary TAR (which stands for tape archive) format to write data to LTO tapes. This means that the data on the tapes written by Phoenix is only accessible from within Phoenix itself. In contrast, one of the benefits of LTO as a storage medium is that it is accessible via LTFS, or Linear Tape File System. This is an open source file system format developed by IBM and supported (more or less) by the consortium of LTO hardware manufacturers. The main user-side benefit of LTFS is that users (and other software) can interact with the files on tape like regular folders.

Long story short, it was not a system based on the principles accepted by the archival community. It was also not a sustainable model for BAMPFA’s digital collections over the long term. Time to get out!

Onwards and upwards

Microservices!

The main alternative model that we looked to was a microservice approach, which stands in contrast to a monolithic program like Phoenix. This approach breaks down each component in the preservation workflow into smaller and (ideally) discrete tasks. Each microservice can then be improved, altered, extended, and deployed as a particular case may require. Archivematica is a high-profile example of an open source digital preservation system using this model, and it’s one that enjoys enthusiastic adoption in the archival community.

As we were considering our options, though, Archivematica seemed too complex to set up with our current staffing, and hosted Archivematica services were way, way beyond our budget.

Not a table, an Inspo board:

| Software | Metadata/Conceptual Frameworks | |

|---|---|---|

| Mediamicroservices (@ CUNY) | OAIS | |

| LTOpers (interface for LTFS-formatted LTO tapes) | PREMIS | |

| IFIscripts (@ Irish Film Archive) | PBCore | |

| UCSB | Local metadata schemas | |

| FFmpeg | “Performace” of digital preservation as an ongoing, iterative activity | |

| MediaInfo |

I started to look at other relevant projects that could help us figure out how to proceed, along with some of the theoretical and technical background that would support the work.

Around the time that it became clear that Phoenix was going to need to go I read a blog post about MediaMicroservices, a project at City University of New York. mediamicroservices uses the Bash programming language in a set of scripts to perform digital preservation activities. In the process of researching this project, installing it, testing it, and playing around with the code I also came across a plethora of other projects on github that became really excellent guides on scripting for AV preservation with a microservice framework in mind.

We also needed to ensure that the metadata associated with our digital preservation masters was robust enough to meet our needs. We looked to PREMIS as a framework to describe preservation actions taken on our digital assets, and PBCore as a container for both descriptive and technical metadata that could be stored with our masters. In the OAIS conceptual model, our stored files and metadata form an Archival Information Package, which is a way of thinking about our master and derivative files along with metadata as a unit so that we can “perform”–as an active verb–digital preservation on them over the long term.

This is one way to look at the underlying task of digital preservation–to nurture an environment in which digital objects can be actively preserved over the long term. This environment includes hardware, software, and also staff labor.

We were able to repurpose a lot of existing hardware and also existing workflows when we decided to abandon Phoenix, some of which is listed here.

- Hardware:

- LTO Decks

- Network Attached Storage devices

- Network hardware

- Commandeer an unused server

- Workflows

- Film collection digitization

- DCP accessions (TBD)

- Digital media/Communications Department productions

- Library audio digitization

We also had to keep Phoenix up and running in parallel to any new system so that we could begin the process of retrieving the terabytes of data that made it into the system, and untangling the mess of which files were backed up onto which LTO tapes. To this end I commandeered an unused computer that had been left over from an unfinished project in our Digital Media department, but I was able to use the LTO decks and the 10 gigabit network routers, switches, and cables that had been part of the Phoenix installation. I also knew that we would want to use storage space on some of the NAS devices on the 10 gig network, at least temporarily.

DIY or die

- Ingest into OAIS-based repository

- Checksums R cool

- AIPs stored on 2 x LTO

- Database records for repo contents, PREMIS events

- Derivatives (& masters) easily searched/accessed

- Transparency = 2 cool

Looking through github, asking for help via email, StackOverflow, and while filing lots of annoying issues on github projects, I was able to articulate more functional specs for what a new system would look like. With these specs in mind, or more realistically, while I was building the specs in my mind, I started installing and trying out different tools that I had found. Mediamicroservices quickly became a top contender as a replacement for Phoenix, since the various scripts it includes cover a lot of digital preservation ground.

The `mm` help screen.

It was clear enough though that mediamicroservices as in use at CUNY was not going to fit into our existing workflows. For one thing, convincing staff to become comfortable with command line tools on top of replacing existing software (however dysfunctional) seemed like a hard sell. The scripts are also built around a command line interface that is intended to be used in interactive sessions on the terminal, with some of the interactivity geared towards workflows specific to the CUNY setup. I had the idea that I could use some kind of a control script and a simple web-based interface to automate calls to ingestfile, which is main script of mediamicroservices.

With some emails to Dave Rice, one of the main authors of these scripts, and some tinkering, I rewrote a portion of ingestfile to allow all the necessary variables and file paths to be declared when calling the script. This also let me suppress the user interview portion of the script, which meant I could run ingestfile from other scripts instead of needing human input. When I was satisfied that it would work at least in my limited test cases, I submitted my changes as a “pull request” to the mediamicroservices project on github.

Very briefly, a pull request is a way for you to ask the owner of an open source repository to “pull in” work that you have done into the source code of the project. This was my very first pull request, and a scary moment because it was the first time I had ever put my newbie coding skills in front of anyone else. But it was surprisingly rewarding, and I was welcomed by some of the contributors to the project with helpful comments and suggestions. This was my first real-live step down the path to contributing to open source software. Even though the pull request never really went anywhere, it was a real eye opener to how easy it can be to make those first steps. For me in particular, getting past the anxiety of talking to strangers was way harder than any of the scripting problems, which makes sense since you are basically asking someone you don’t know to let you make changes to work that they have spent unknown hours refining. But reaching out with some degree of humility and doing as much of your own research in advance will go a long way towards making open source pals.

Open Source digital asset management

At the same time, another awesome tool that I came across is a Digital Asset Management System called ResourceSpace. This is also an open source project, and one that seemed well suited to our access needs. It also has a fairly well documented API, or Application Programming Interface, which would allow us to add assets and metadata programmatically. Coincidentally it turns out that CUNY also uses ResourceSpace, which was a great selling point for my boss, who was glad to hear a testimonial from a known colleague. I saw ResourceSpace as a front-end for the digital preservation nitty gritty that would happen behind the scenes, with access copies and descriptive metadata posted to the DAMS along with identifiers that could link an asset to the preservation metadata stored in MySQL, along with information we would need to retrieve an AIP from LTO tape.

It only took a few days to get a working proof of concept up and running in PHP, including calls to our FileMaker collection database and posting derivatives into ResourceSpace. Mediamicroservices is written in Bash, but I was more familiar at the time (and I still am) with Python, another relatively approachable programming language. My “control script” that I mentioned earlier was written in Python. This is what was running the Bash scripts, as well as the MySQL calls that would add database records for assets and PREMIS-based actions. The web interface I made for it was written in PHP. This worked, sort of, but one of my appeals for help on StackOverflow produced my favorite piece of advice that I have ever received.

"The worst coding style one can ever met."

Even though the commenter was being kind of a jerk, he wasn’t necessarily wrong. Eventually I wound up rewriting a lot of the core functionality of mediamicroservices in Python, and found an Python-based open source web application framework, called Flask, that provided a more robust way to handle the interaction between users and the scripts doing the digital preservation heavy lifting. I also wrote python scripts to replicate functionality from LTOpers, which is another AMIA-linked project that lets you interact with LTFS. This gave us a consistent way to write data to and retrieve data from LTO. The Flask app also handles all the queries to our collection database, creates records in our preservation database, and posts assets and data to ResourceSpace. The result of all this is a repository we have in place that meets our more detailed functional specs.

HI I'M EDITH

I named the system EDITH in honor of Edith Kramer, the PFA’s director from the 80s until 2005. She has an incredible memory, and is a also an huge advocate for film on film and hates that I named a digital preservation system for her.

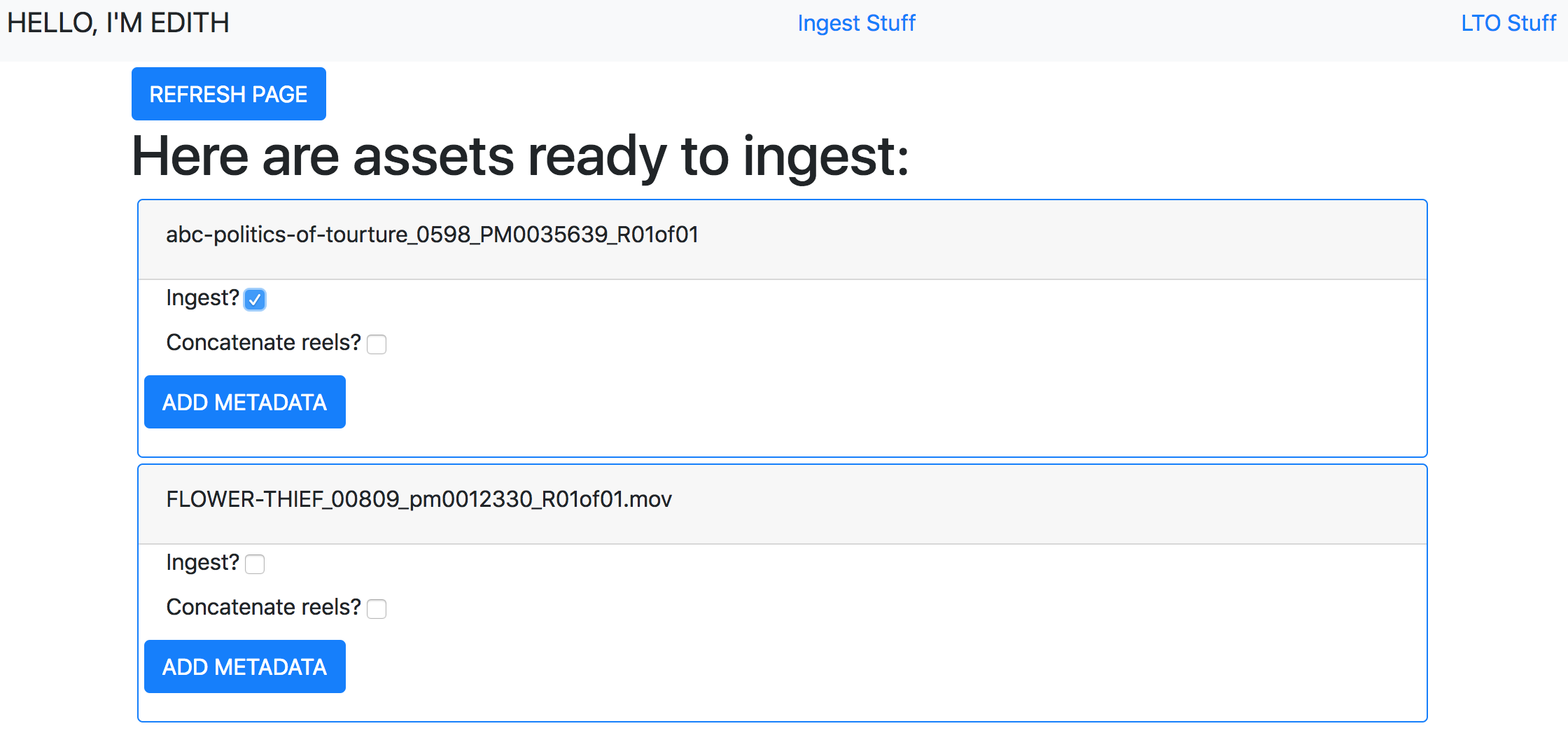

Here’s a screengrab of what the interface for selecting assets to ingest looks like, and I’ll just say that we’re in the process of getting it up in production. Both the Flask webapp and the digital preservation scripts are in what I would call a Beta state, but are up and running.

What is our state of care? Our capacity for care?

Now I’d like to look inward a little bit and think about the the process of getting to this point and assess our “state of care” that I mentioned at the beginning of my talk. At a really basic level there is a cost/benefit question that asks of a project like this “IS IT WORTH IT.” But I think that there are also some important questions to ask here that are informed by authors who describe a feminist ethics of care. I won’t go into that very deeply here, but I’ll mention the concept as a point of reference. In short, an ethics of care puts justice and responsibility towards others at the center of ethical considerations. In this model, no individual is acting alone, in an isolated universe of Platonic ideals, but everyone acts in a world in which historical injustices and power imbalances are recognized as bringing us to our current state of affairs.

Earlier on, I mentioned care towards our collections, which is at the center of our archival work. But I also mentioned the environment in which that care takes place, which includes the ways that our collections arrive under our care, the infrastructure that surrounds the work being done, the software in use, and also the staff who perform the work. An assessment of our project in this light has to consider these elements in relation to broader questions of justice, and economic as well as human sustainability.

In terms of the economic impact of this project, there were some upfront costs that were supported with funds from various grants that would be impacted by this work. For example we bought a new server for something around $6000, which hosts the Flask app and our Resourcespace instance, as well as handling the transcoding of video files, and it also interfaces with the LTO decks.

- New stuff

- Server ($6K)

- Drives

- Cables

- PCIe cards

- Probably more?

There have also been considerable staffing costs in terms of my time spent over the last few months setting up the various scripts, testing, and coordinating with staff. We have a small office, so my time diverted from other responsibilities has a real impact on our work.

- Staffing

- Michael’s time

- Testing time

- Training time

- Planning meetings

- Probably more?

There are also unknown future costs that we can at least try to plan for. I’ve been more closely involved in this project than anyone else on staff, so what happens if I get hit by a bus tomorrow? Who is going to maintain the system and fix things if something breaks? Do we have sufficient interest and buy in from staff who are doing digitization or creating born-digital materials so that there is a critical mass of people interested in seeing the project succeed?

Documentation is a hug for the future

Some of the safeguards that are in place include having had conversations with staff over the past year about the project and building internal goodwill, and also making sure that this new system is built with the real world needs of staff from the outset. Another incredibly important element has been to document as much of the new system as possible. That means documenting the code, but also writing out high-level explanations of how the system works. Documentation of a coding project is a way of creating relationships with people in the future, who may very well end up being you.

OK, now for one last question/slash/this should have been done differently. If I’m going to reference a feminist ethic of care, I have to ask what role my gender, race, and class played in my ability to butt into my institution’s discussion of how to address the problems we faced with Phoenix. Technically it’s outside of my job description to manage this kind of project, and I feel pretty certain that a staff member who identifies with more marginalized communities would have had a more difficult time a) feeling entitled to propose the kinds of changes I put forward, or b) getting listened to in the face of an ambitious project that seemed far from possible at the outset, and has faced its fair share of technical roadblocks. I have to take some responsibility for taking advantage of that position, even though we have gotten what I see as a good deal of benefit from it.

Is it worth it?

So has it been worth it? I would say yes, but obviously there are things that I learned along the way that I would have done differently. We have extracted ourselves from an expensive proprietary system that not only failed to serve our needs, but also profited from a relationship to a militarized surveillance state. We have been able to fund at least a little bit of work to add functionality to MediaInfo, which will hopefully start a precedent for our use of tools made by people we respect. We are doing better by our collections, and hopefully we have tools that we will be able to sustain and improve, and yes, eventually ditch in favor of something better.

Thanks!

Resources

- AMIA Open Source

- Mediamicroservices

- IFIScripts

- BAMPFA stuff

- More on ethics of care:

- Michelle Caswell & Marika Cifor, 2016. From Human Rights to Feminist Ethics: Radical Empathy in Archives. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0mb9568h

- Rachel Mattson, 2016. Can We Center An Ethics of Care in Audiovisual Archival Practice?