Digital preservation spelunking: Kodak PhotoCD, PICT, and image file normalization

The original title for this post was going to be “How to quickly normalize PICT files using ImageMagick,” but the files (created in 1997!) I was working with turned out to be something much more interesting. I asked a student to rip some image files off of old CD-Rs and stumbled across a digital forensics mystery and learned about a digital image ecosystem I had never heard of!

TL;DR I found some neat images on a CD-R that turned out to be an old 1990s Kodak proprietary image format buried under some layers of ’90s Mac OS wrappers. They can be successfully resurrected!

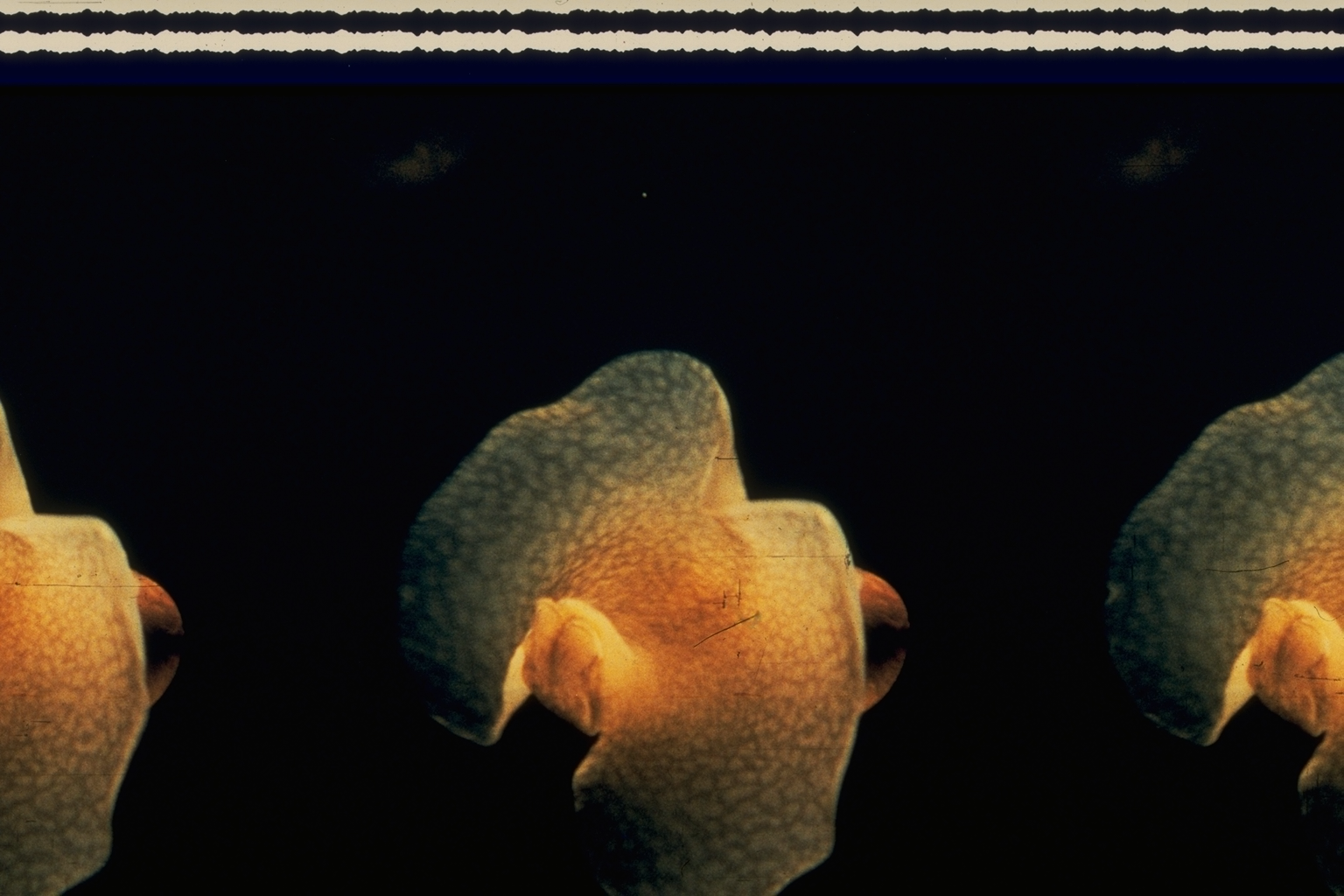

All Jean Painlevé images are copyright Archives Jean Painlevé and courtesy BAMPFA.

All the files

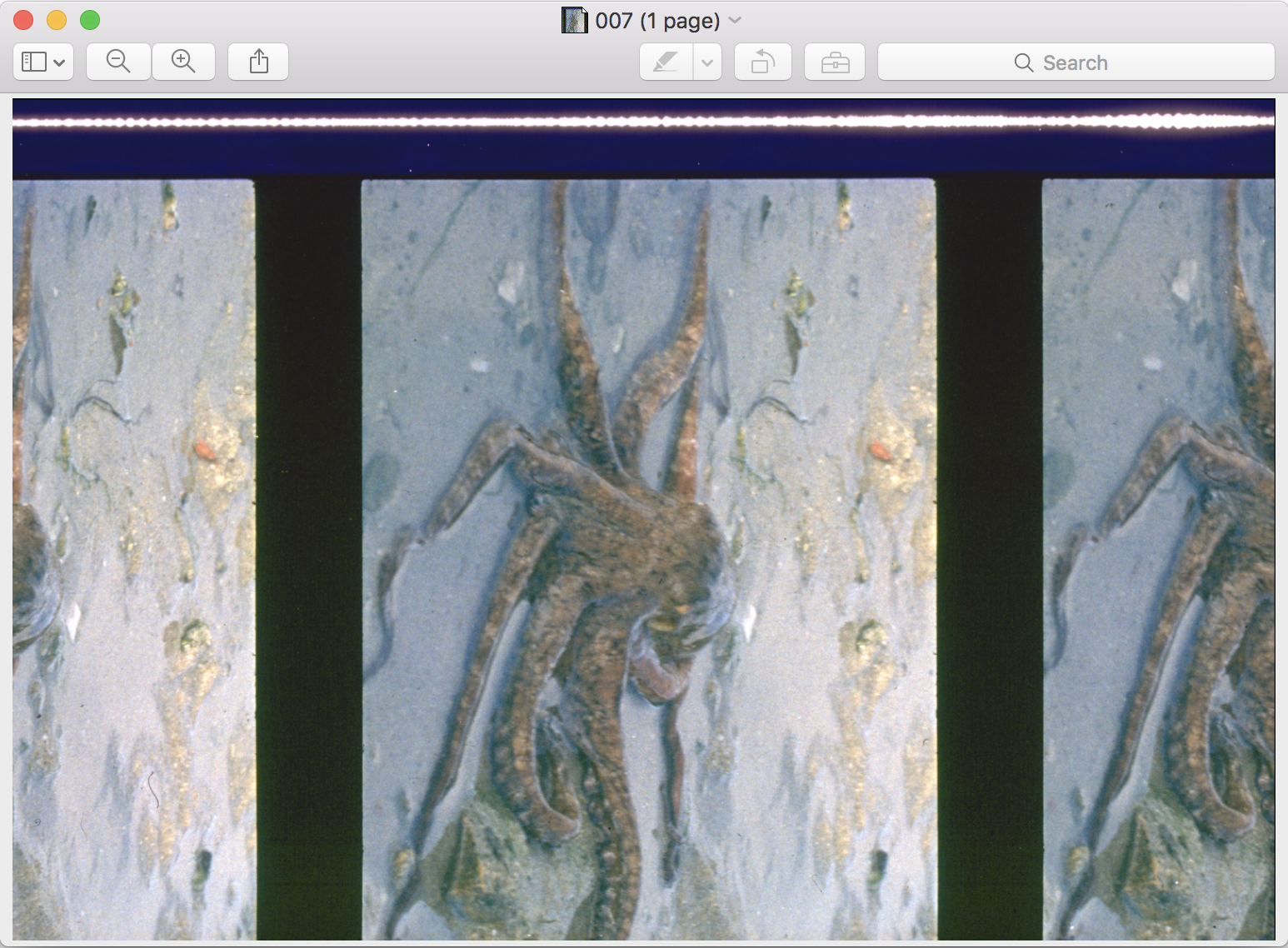

I was working with a student employee this week to get images off a bunch CD-Rs from the early 2000s. Most of these contained film stills used in BAMPFA printed program guides and/or our website, and had been hovering near the bottom of my to-do list for… a long time. One odd outlier, though, was a CD-R marked Painlevé #6, which contained about 600MB worth of still frame scans from Jean Painlevé prints. Our student employee called me to her workstation and showed me a bunch of files that were viewable in the Mac Finder and could be opened with Preview, though the controls for zooming and all the options for saving or exporting (except as PDF) were greyed out.

All the controls are greyed out :( sad octopus

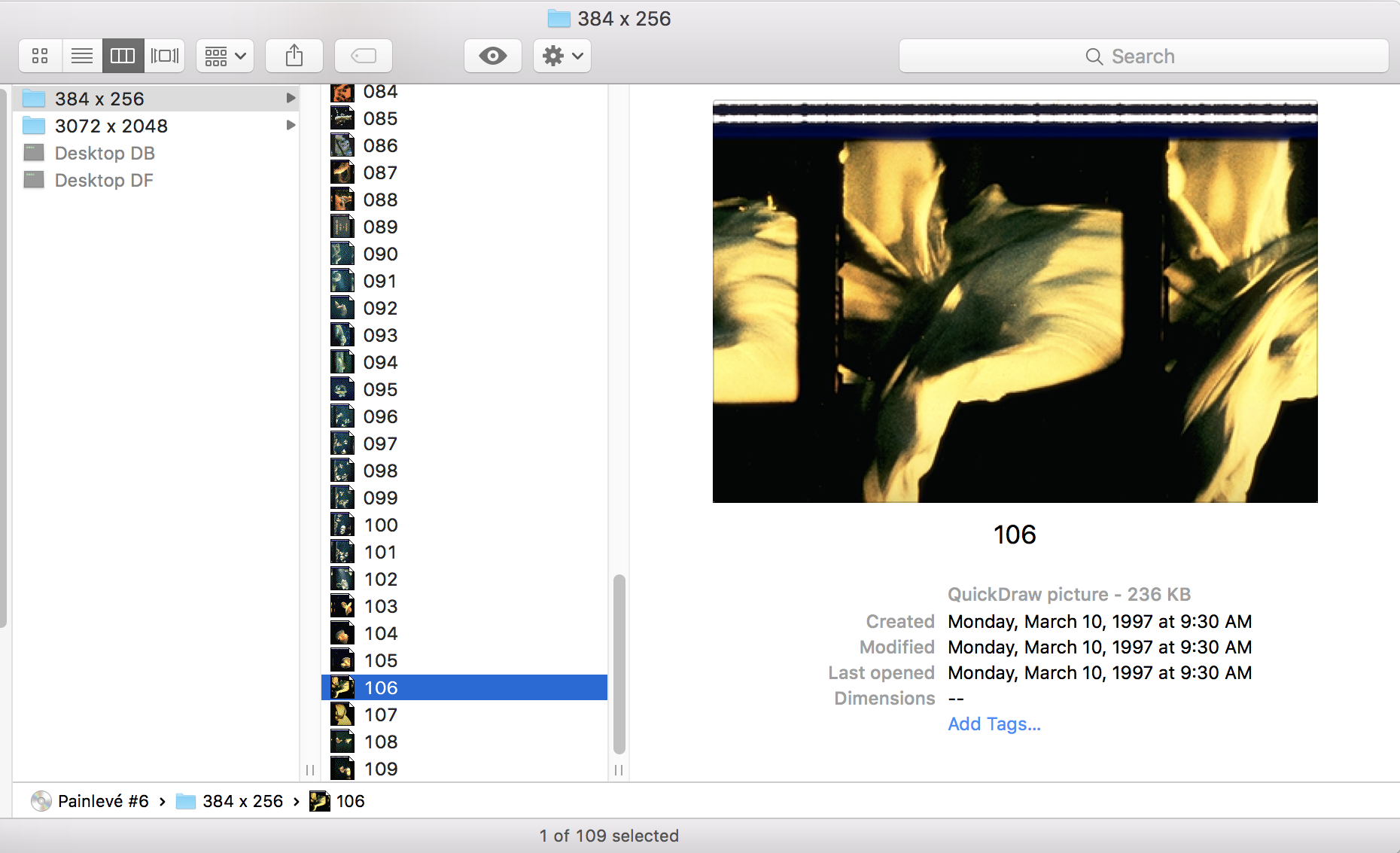

The CD-R itself was unremarkable, but the files indicated that they were made in 1997 and an inkling in the back of my mind warned me that there was bound to be something weird going on here. The folder strucure on the CD looked like this:

Note the dates, the previews, and the hidden files!

I asked the student to rename the extracted files and I thought I’d show her how to use ImageMagick (a really powerful tool you should try out if you work with images!) to convert the images to TIFF for ingesting into our digital asset management system. Here’s what came out of that first pass:

I see a black TIFF and I want it painted normal...

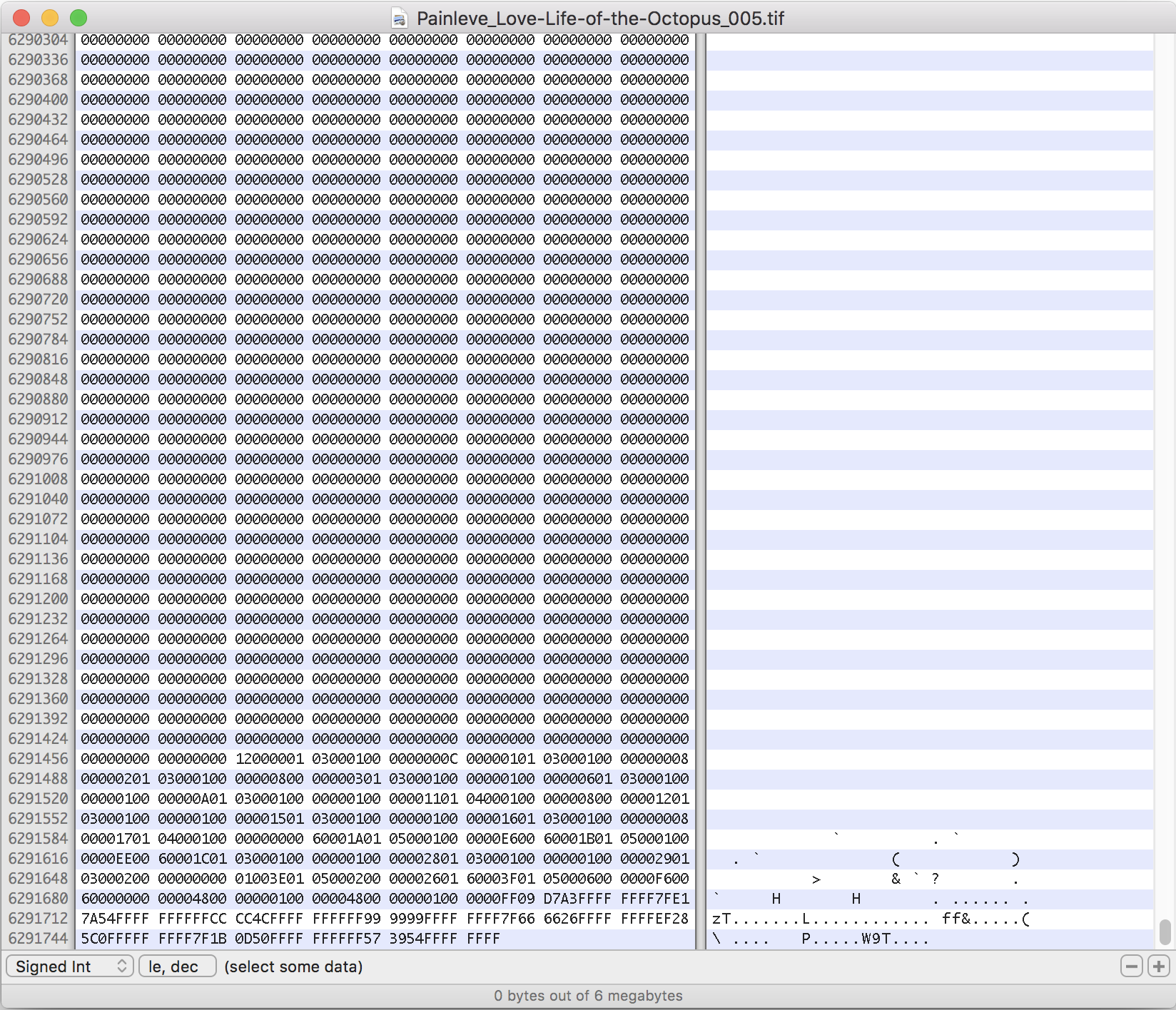

… Hm. Opening the TIFF file in a hex editor (which is a really awesome type of tool I’m just really getting to know, and lets you see the innards of a binary file like an image) showed me that the command magick convert Painleve_001 Painleve_001.tif output a TIFF file with 6MB worth of zeros:

... garbage out ...

I tried all manner of options with my magick command, but all with the same result. I reached out to the IM user forum to see if anyone had any suggestions, and also on Twitter to see if #digipres Twitter had any experience with PICT files. Both turned out to be excellent resources! In the mean time, I started reading up on what exactly the PICT format was, and tried to figure out if maybe the files were just corrupted in some way.

The PICT file format originated in the early 80s as the native “metafile” format (still not totally sure what that means) for Apple’s QuickDraw, the graphics core of the pre-OSX Mac operating systems. The format was used until well into Mac OSX, which still supports it in a limited capacity (which is why I was able to preview them!), though Mac applications after OSX 10.8 balk at extracting the image data or even opening them (see the QuickDraw article for more details!). PICT was a way for applications to represent graphical information to the GUI using the QuickDraw API, and also perhaps to exchange graphical information between applications. From the Apple developer documentation:

QuickDraw provides a simple set of routines for recording a collection of its drawing commands and then playing the collection back later. Such a collection of drawing commands (as well as its resulting image) is called a picture. A replayed collection of drawing commands results in the picture shown in Figure 7-1.

Figure 7-1 A picture of a party hat

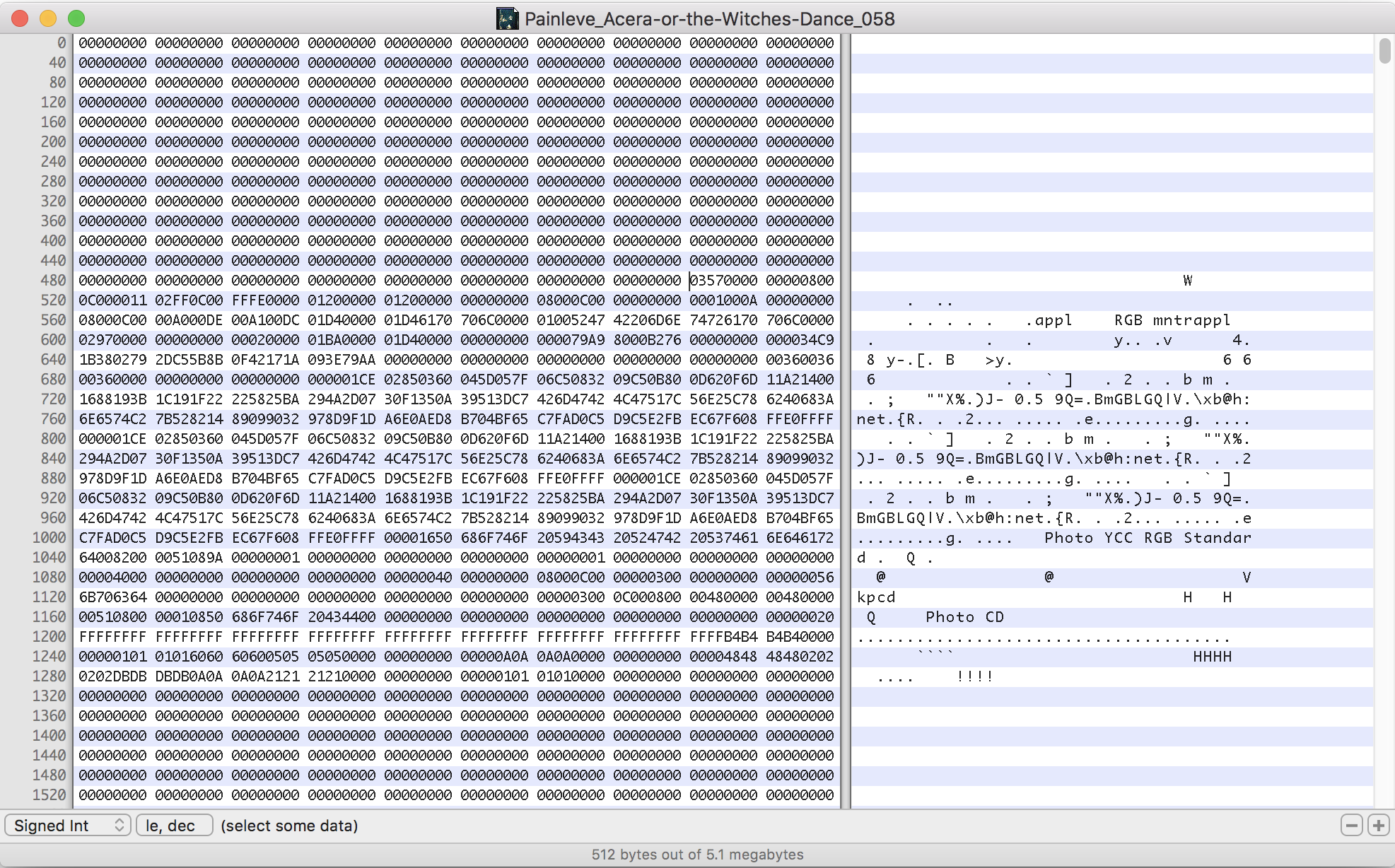

Its structure defines opcodes (low-level computer instructions) for the representation of vector graphics on-screen, but also allows for a bunch of other stuff, like bitmapped graphics information, and some types of textual metadata (more on that shortly). Apple had the foresight to include some reserved opcodes that allowed the format to be extended into the 90s, which lets things other than vector graphics to be included in the byte stream (and more on that shortly too). For my immediate needs, I learned that version 2 PICT files (developed in the mid-80s) have a “magic number” of 00 11 02 ff 0c 00 at offset 522, that they end with 00 FF, and also that they have 512 bytes of zeroes at the file header. Looking at my PICTs with the hex editor confirmed that they were really PICT files and that they seemed fully kosher. What else could be going on here?

512-byte empty header, plus the magic number, plus some extras

One of the first clues to how complex my files were is buried in the above image. Down in the PICT metadata is the phrase “Photo YCC RGB Standard,” which a Google search later revealed to be a color encoding method developed by Kodak for compression with chroma subsampling (plot=thickened). There is also a phrase at the end of the file noting that “Quicktime(tm) and a Photo CD Decompressor are needed to use this picture.” OK, QuickTime I get as a 90s-era requirement, but WTF is a Photo CD Decompressor? Here was another clue–running exiftool -verbose on one of the files revealed a DEEP set of tags with lots of crazy information, including Tag 0x8200, CompressedQuickTime (CompressedQuickTime): followed by a lot of image metadata including compressor (string[31]) = Photo CD.

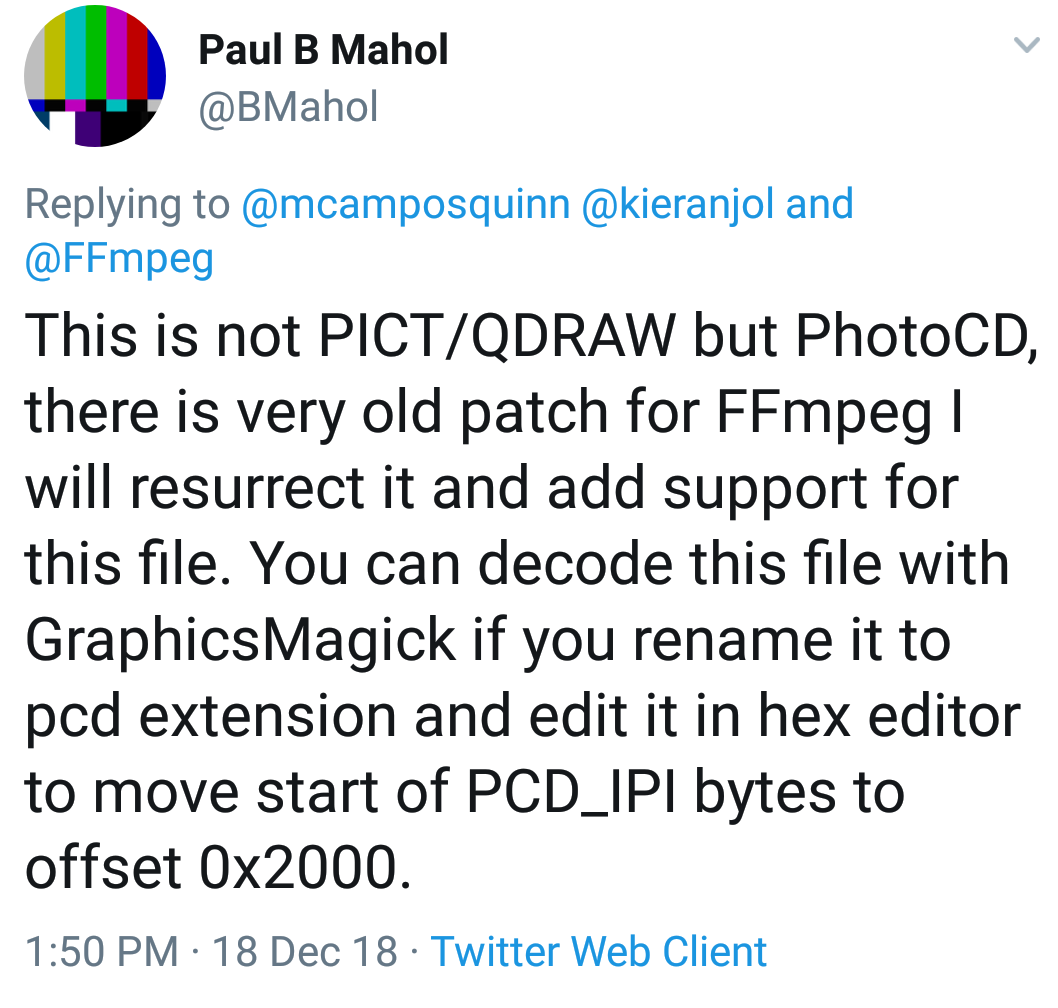

I was busy ignoring these clues, but at about this point, Kieran O’Leary had reached out on Twitter to one of the FFmpeg developers, Paul Mahol, who definitively identified what was going on here. We struck gold!

mind=blown

I had never even heard of that file format, so suddenly all the tidbits I had seen with the various tools I had tried started to fall into place. But I still couldn’t figure out quite what to do with the images. Moving the string PCD_IPI, which I could see in the hex editor, to the correct position (PhotoCD expects the string at byte 2048 to constitute its magic number), and also deleting all the extraneous PICT bytes resulted in a file that registered according to exiftool as a PhotoCD format file. I was also able to get ImageMagick to convert the resulting file to a PNG (another raster graphics format with lossless compression, more on that later!) if I added a “.pcd” extension. But working through over 100 images like this didn’t seem feasible or appealing.

What the heck was a PhotoCD in the first place though??

A Kodak Photo CD. "Photographic Quality Images." Public domain image from Wikipedia.

It turns out that in the early 90s Kodak developed its own ecosystem of film scanning and digital image display, including everything from a supply chain of proprietary scanners and CD players to custom colorspaces and encoding algorithms. You really have to admire the grandiosity of Kodak’s vision. In this scheme, photo labs and consumers (evidently a pro-sumer intended user?) would all partake in the Kodak walled garden for digital images. People were supposed to take their exposed 35mm film to a PhotoCD-equipped lab, which would develop and scan the negatives for them, and return a CD with up to 100 (!) images available at several resolutions, with the master scan done at 2200 ppi. Included within each PCD file were each of these derivatives along with metadata about the image, the scanner model and date, etc. WOW! So weird.

You were then supposed to look at the images on a TV screen using a CD-i player (wha??) or a PhotoCD-enabled player equipped to read the encoded files. The quality of the images could be quite high (FADGI recommends 2000 ppi for “two-star” scans of 35mm negatives), and I’m really curious about the consumer opinion of this system at the time (how many people were able to use files like this at the time, and how did they use them?). Ultimately the system seems to have been overtaken by the explosion of cheaper digital camera technology around 2000 (and according to Wikipedia, problems with color rendering and also the preponderance of JPEG and PNG as more open and easier to use standards by the late 90s). I was alive and well in the 90s and I had never heard of the format, so…. go figure.

I also started doing some more reading and found references on a Corel Paint user forum (from 1998!) and on a PhotoCD enthusiast’s personal site to some weird stuff that happened when you tried to open a Photo CD on a Mac.

tedfelix.com, just a cool website

Meanwhile on the ImageMagick forum, someone humbly recommended this little utility he wrote that was coincidentally able to read my weirdo PICT files. This utility is called deark and it is fucking incredible. It can read and parse dozens of obscure old file formats including many Amiga and Atari graphics formats, and either convert them to modern analogues or extract files embedded within them, which was crucial in my use case. Specifically, deark (de-ark? d’yark? deer-k?) can see that the opcode 0x8200 mentioning CompressedQuicktime contained the data payload that I was interested in, extract that data as a QTIF file, then extract the enclosed “normal” PhotoCD file buried within. Given that file, I could use ImageMagick to extract one of the embedded layers (remember that PCD includes 6 levels of the image?) and convert it to PNG. Unfortunately, PCD to TIFF directly resulted in messy color errors–take a look at the math behind YCC color encoding… yikes! The resulting PNG is then able to convert to TIFF for storage. The command sequence looks like this:

michael$ deark Painleve_Acera-or-the-Witches-Dance_056 # <-- run deark on a PICT file

Module: pict

Format: PICT v2

Writing output.000.qtif

michael$ deark output.000.qtif # <-- run deark again on the output QTIF file

Module: qtif

Writing output.000.pcd

michael$ magick output.000.pcd[6] output.png # <-- run imagemagick

michael$ magick output.png output.tif # <-- convert the PNG to TIFF

To get a sense of the file compression involved in the PhotoCD, the original PCD file transformed in the commands above was 5.3MB. The intermediary QTIF file and the PICT wrapper accounted for only a negligible number of additional bytes as a layer above the PCD. The PNG I extracted from the PCD expanded to 26.4MB and the TIFF was 27.9MB! The other five derivatives included add up to 2.9MB as TIFFs made with the same process, or 30.8MB total. That’s a 5.8x savings in space… neat!

Happy octopus!

The metadata I can now read from the previously hidden PCD files is also pretty cool, and includes information like the scanner model, the algorithms used to reproduce the color and exposure characteristics of a particular film stock, and more. Check it out:

File Type : PCD

File Type Extension : pcd

MIME Type : image/x-photo-cd

Specification Version : 0.6

Authoring Software Release : 4.13

Image Magnification Descriptor : 1.0

Create Date : 1997:03:08 11:40:15-08:00

Image Medium : Color reversal

Product Type : 052/70 SPD 0000 #00

Scanner Vendor ID : KODAK

Scanner Product ID : FilmScanner 2000

Scanner Firmware Version : 3.56

Scanner Serial Number : 0127

Scanner Pixel Size : 11.48 micrometers

Image Workstation Make : Eastman Kodak

Character Set : 95 characters ISO 646

Photo Finisher Name :

Scene Balance Algorithm Revision: 6.2

Scene Balance Algorithm Command : Neutral SBA On, Color SBA On

Scene Balance Algorithm Film ID : Kodak Universal E6 auto-balance

Copyright Status : Not specified

Orientation : Horizontal (normal)

Image Width : 3072

Image Height : 2048

Compression Class : Class 3 - Text and graphics, high resolution

CSI: DigiPres

I was also able to get a sense of the forensic history of my files:

- In 1997, someone commissioned a lab to scan three 35mm film prints to get frame enlargements.

- The lab provided a Kodak PhotoCD with more than 100 images from the three films.

- Someone else (it isn’t clear where the prints or the files came from–they’re not from the PFA collection) extracted the files on a Mac using the regular CD(-ROM?) drive.

- At this point, Mac OS9.x wrapped the files as PICTs and enclosed the data payload under the

CompressedQuicktimetag of the PICT files using opcode0x8200 - The PICT files extracted from the original Kodak CD were then burned onto a CD-R and left untouched for at least 15 years.

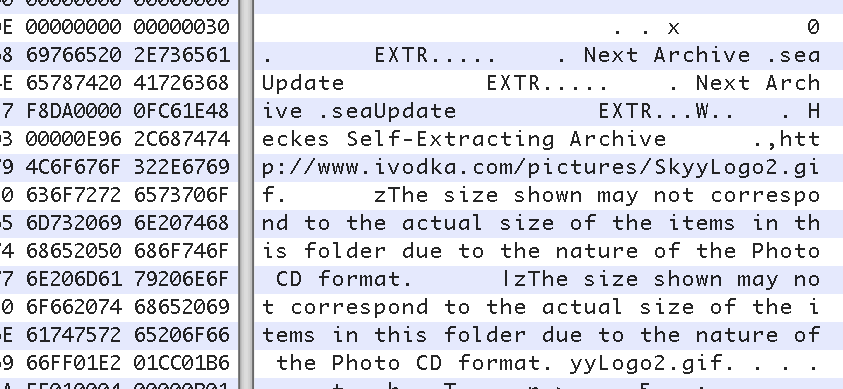

Also, check out the note in the “Desktop DB” file included on the CD-R, presumably written by Mac OS9:

"The size shown may not correspond to the actual size of the items in the folder due to the nature of the Photo CD format."

I had never seen anything helpful in those hidden system files until now!

Next steps

I might write a script to run the conversions metioned above for all the files I have. There are not really that many, but it would be a good way to finish this exercise. Ultimately, I doubt I will ever run across these kinds of files again, but this has been a cool chance to learn more about file encodings, weird consumer product history, and extend my comfort level using hex editors. Paul Mahol also mentioned resurrecting a patch in FFmpeg to read PICT files, so I will totally give that a shot too!

There are other tools that can be used to convert PCD to modern formats, but I haven’t had time to check them out. The most commonly referenced one is pcdtojpeg.

Thanks to everyone who helped in this learning journey: Paul Mahol (ffmpeg), Jason Summers (deark), Kieran O’Leary, Fred of ImageMagick fame, and Kirby Lima, our workstudy student who noticed they were weird in the first place!

References and further reading

File format overviews:

http://fileformats.archiveteam.org/wiki/QTIF

http://fileformats.archiveteam.org/wiki/Photo_CD

http://fileformats.archiveteam.org/wiki/PICT

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PICT

Apple documentation about PICT:

Macintosh File Format & Picture Structure for Graphic Applications

Tools

https://github.com/ImageMagick/ImageMagick/issues/970

https://imagemagick.org/discourse-server/viewtopic.php?f=1&t=35205

Kodak PhotoCD resources

TedFelix.com (this is incredible!)

Urrows, Henry, Urrows, Elizabeth. Kodak’s Photo CD and Proposed Photo YCC Color Standard. Computers in Libraries, v11 n4 p16-19 Apr 1991.