Archiving microcinemas on paper and online

Bay Area underground

Artist-run microcinemas have been a feature of the Bay Area experimental/avant-garde film scene since at least 1960 when Bruce Baillie, Chick Strand, and company began Canyon Cinema.

Earlier more-or-less underground Bay Area screenings included the Vortex series run by experimental animator and O.G. freak Jordan Belson with tape music head Henry Jacobs between 1957 and 1959 in the planetarium of the then-stuffy California Academy of Sciences (the eggheads canceled the series just as it was getting good, but it arguably led to the SF psychedelic light show scene of the 60s). From 1946 to 1955, filmmaker Frank Stauffacher ran the Art in Cinema screening series at what was then the San Francisco Museum of Art; it was one of the first major series of avant-garde cinema screenings on the West coast (SFMA later became SF MoMA, which in 2021 jettisoned its film program altogether–the circle of life, baby).

The ensuing decades saw San Francisco and the Bay Area generally become a place for experimental film. San Francisco Art Institute (pour one out), the California College of Arts and Crafts (which in 2003 dropped the ‘craft’ from its name and this year abandoned its historic Oakland campus in favor of that sweet, sweet speculative real estate capital), and even UC Berkeley churned out hordes of influential and ~important~ filmmakers.

Up (and out) the punks

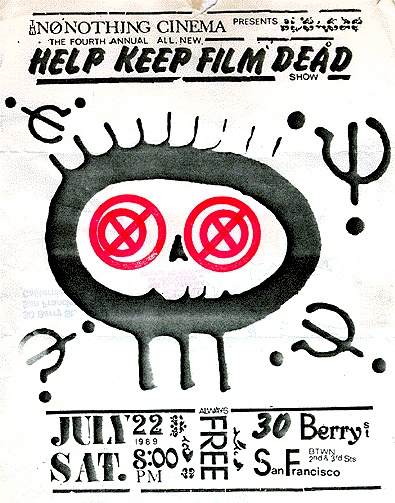

In the 1980s and 90s, punk and DIY scenes in SF and the East Bay created new (though adjacent) communities, with shows taking place at punk venues and warehouses that occupied formerly derelict commercial and industrial spaces (results of white flight, globalization and the deindustrialization of American labor, and “urban renewal” planning of the 1950s-1970s). No Nothing Cinema was arguably the best known of these microcinemas, but others included Club Generic, which was run by the late, great Stephen Parr, who also founded Oddball Films and ran regular underground screenings in its archive until his death in 2017.

Taken from here

By the 2000s in the Bay Area, the affordable spaces occupied by (largely white) artists and punks became prime real estate for investors hoping to develop luxury condos and related amenities. The punks, willingly or not, became part of the “charm” attracting gentrification, slowly pricing out people of color from historically Black and Brown neighborhoods and making affordable warehouse spaces increasingly scarce. The Ghost Ship fire in 2016 accelerated the closure or eviction of existing artist spaces and made it even more difficult to start new ones.

All of which is to say that each wave of gentrification, from the 1980s to the present, has made artist run spaces (which are inherently ephemeral anyway, often by design) ever more precarious.

Check out this 2011 interview with Fred Frith at the closing of 21 Grand in Oakland:

Lisa Hix: Where will the scene go?

Fred Frith: It’ll be the same as always. New places will no doubt spring up until they get closed down for whatever reason, all run by the artists themselves until they run out of energy, or money, or allies, or luck, just like always. And of course there are other local places that will continue to support music without necessarily specializing in “niche genres” – The Lab, Meridian Gallery, East Nile, The Uptown, The Starry Plough. Otherwise they’ll go to perform wherever they can get a decent gig, which usually means not around here! I can name at least a dozen top ranking musicians who’ve left the Bay Area within the last two years because of how bad the situation has become here, and there are probably a lot more than that. We need half a dozen 21 Grands, and a media that actually shows up and takes note, and let me applaud the honorable exceptions to that statement!

Plus ça change, right?

Ephemera & ephemerality

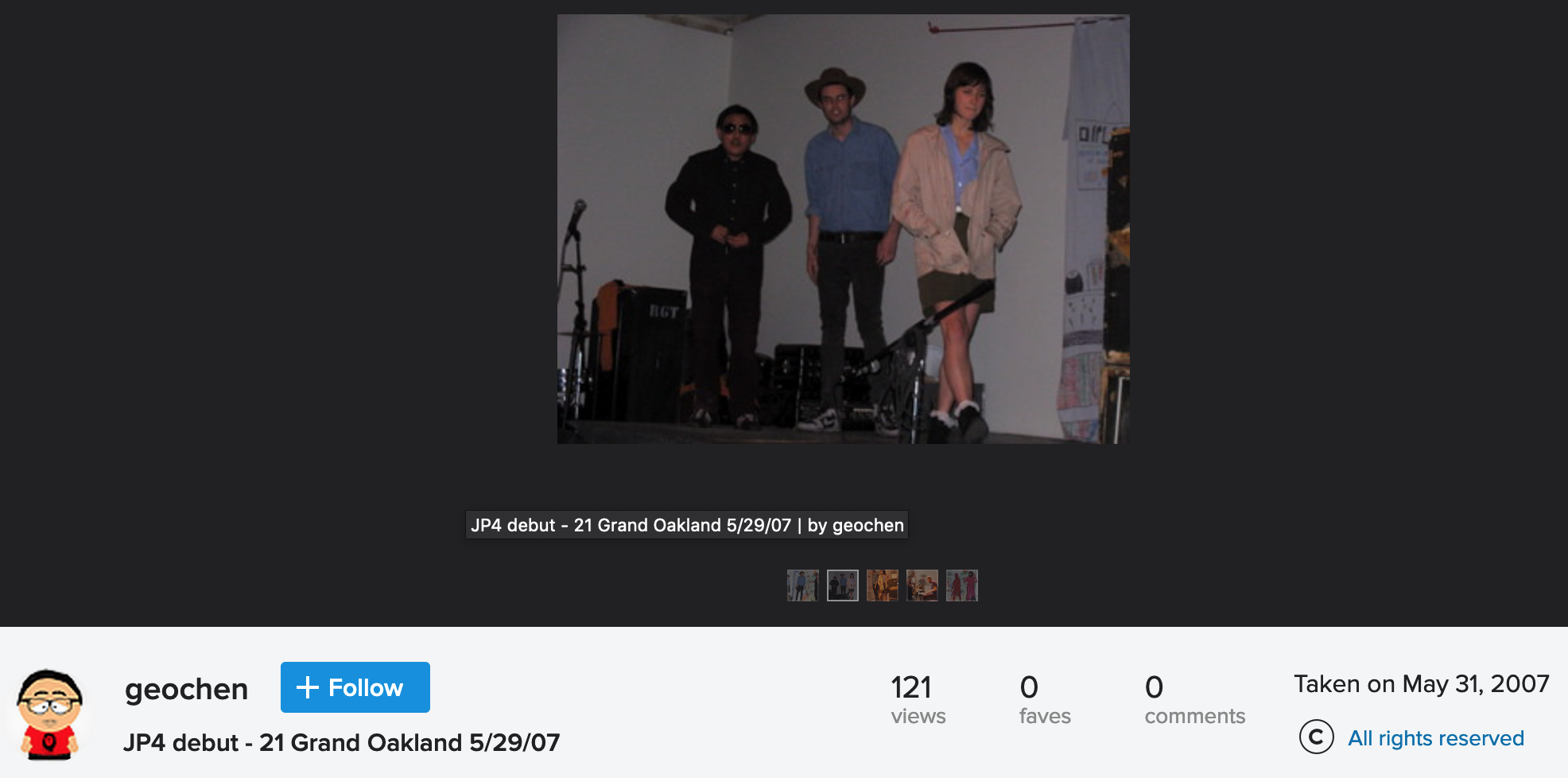

Maybe it needs to be said explicitly: that shit sucks! The vibrancy of artist-run spaces–both the ability to take risks in presenting or performing new work, and in just hanging out with like-minded people–is very often (speaking subjectively, I suppose) one of the most powerful forces sustaining a community of artists. Future groups of artists should be able to get a sense of how a collective or venue worked at a particular moment in time. Flyers, photos, videos, and tapes from the 80s and 90s punk scenes give us a sense of how underground artists worked in the face of Reaganism, Bush Sr., and Clinton neoliberalism. Crappy cell phone photos from the late 2000s give us a sense of what it was like to be an artist during the Great Recession.

It says "photo by George Chen," but he's in the picture, so... From here.

One of the great things about artists promoting their own spaces and their own work is that they usually come up with interesting or at least cool-looking ways to attract people to shows. Unfortunately, punks are also not known to be great at keeping track of their stuff between evictions, or thinking of the future when they create ephemera–like is that date supposed to be November 1st 1995 or 1999??? Did you really give away the last copy of your flyer??

As an archivist, one of my life goals is to be able to actively collect this kind of ephemera while it’s still fresh, and hopefully capture some of the juicy contextual metadata from the creators themselves while they’re still thinking about what they’ve done (or while they’re still alive as the case may be). And of course, here in 2022 ephemera is much less heavy on flyers stapled to telephone poles and more geared towards social media. But when Twitter feeds can be years old with hundreds or thousands of posts, where do you even start? A good collection development plan includes statements on what not to collect, as well as how much of completist you should try to be.

Luckily a good candidate for this kind of collecting practice developed in 2021. Justin Clifford Rhody, a filmmaker and former resident of the Bay Area who is now based in Santa Fe, New Mexico, joined with other Santa Fe artists in 2021 to create No Name Cinema, an explicitly anticapitalist, “no-profit” operation. According to the group’s website, they “are working to assist an artistic community in New Mexico that exists outside of the museums, beyond the schlock of Hollywood and is truly a people’s cinema.”

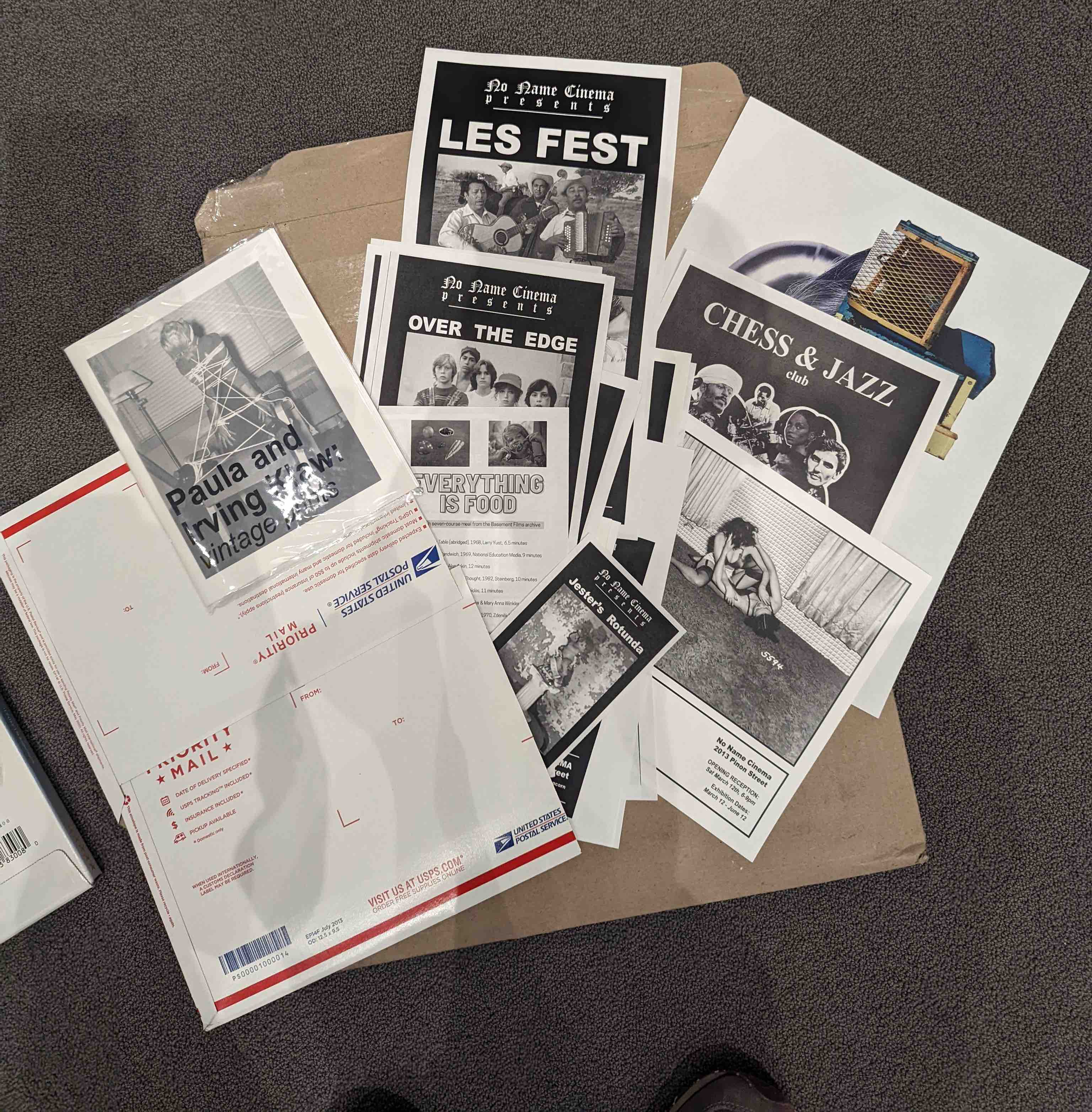

In early 2022 I reached out to Justin to suggest that PFA should collect the No Name ephemera and a few weeks later I got this awesome package in the mail:

Good mail day!

In just a few months of programming they had already created dozens of flyers! Holy smokes! They also have a pretty robust Instagram presence and a website that seems to be updated pretty regularly with upcoming programs. This quantity of content seems pretty manageable at this point, so a multi-pronged approach should be doable. I decided that for this collection at least we would have an online finding aid in addition to web captures of their online presence. The paper material is easy enough: organize it chronologically, write a little description, put it in a box, done (y’know, more or less). What about the web stuff?

Here’s where things start to get ~interesting~.

That’s WACZ!

Everyone knows about the Internet Archive and the Wayback Machine (or at least I hope you do? If you’re reading this you must), but in the last few years the fine folks at Webrecorder–shoutout to Ilya Kremer in particular–have been tirelessly developing tools to put web archiving in the hands of regular people. While the Wayback Machine and similar crawlers cover the World Wide Web at a huge scale, constantly, repeatedly, they can never capture the level of fine detail that might be required to reflect the nuances or full context of an artist-run venture. Very often, automated crawlers will ignore one page or another on a site for cryptic reasons, or will capture a JPG thumbnail but not be able to click through the JavaScript tool that lets you access the larger version of an image. With a clearly defined collecting scope (this is really crucial!) an individual institution or an individual archivist can set out to collect a particular organization’s site on a regular schedule, hopefully capturing updates as they appear. Again, the PFA Library’s scope needs to be strictly defined in advance of setting out bright-eyed into the wide Internet since we’re not able to (or interested in) recreate the Wayback Machine.

While the Webrecorder project does create tools for developers and people working on large-scale automated projects, two tools in particular are geared towards more or less regular people: ArchiveWeb.page and ReplayWeb.page. As the names suggest these two tools are for capturing sites and then replaying the bundle of files each capture creates. Since 2008, the WARC format (standing for Web ARChive) has become the default standard for storing recorded websites. It’s a fancy version of the more common .zip archive format. Basically all the files (html, css, javascript, images, etc.) needed for a browser to “play” a website back are in there, along with metadata that helps the browser work with the files.

In 2021 the folks at Webrecorder released version 1.0 of the WACZ format, which extends the WARC format. According to Webrecorder, “WACZ stands for Web Archive Collection Zipped, and is a new file format designed to make creating and hosting web archives quicker and easier.” I’ll just let them explain the main advantages:

Because WACZ files are essentially Zip files, they benefit from a property of Zip files allowing them to be read on-demand over network without downloading the entire file. WACZ files they come packaged with everything you need to create and host a web archive collection: A random-access index of all raw data, a list of entry-point pages into the archive, and a user-defined, editable metadata about the web archive collection. As an added bonus, the full-text data extracted from web pages is also included, ready to be ingested into search engines like Solr or loaded on-the-fly along with the replay.

Wow!

OK, now what? Using the ArchiveWeb.page desktop tool (it also comes as a Chrome extension!), I can just head to my favorite website, hit record, and click away. There’s an “autopilot” function that takes over the browser and clicks through everything it finds on a page, but I find it more reliable to manually click through everything. Everything loaded by the browser when you record gets saved and is replayable by the browser on the other end.

Now for the really cool part: the code in ReplayWeb.page lets you take the WACZ file you created and embed it into another web page, where you can browse the captured site in its own little window (or full screen). This means that it’s perfect for including on CineFiles! I did some retooling of the code behind CineFiles with help from Berkeley IT colleagues and now we can include web archives as one of the types of ephemera we collect and index. Sharp-eyed readers will notice that the Webrecorder description of WACZ suggests taking the full-text data the format includes and putting it into Solr, which just happens to be the search index we use for CineFiles :) One thing we’re working on now is a streamlined process to take the full-text files (stored as JSON-L) and include them in our search index.

Bringing it all together

Now that we have the paper materials described in a finding aid, the website and Instagram feed archived and displayed on CineFiles, and a solid working relationship with the No Name crew, we should be good to go, at least for the moment.

Given the uncertainty suffusing the last couple of years and the precarity that so many have experienced (especially artists working actively against capitalist modes), we can never speak in absolutes about what we will or will not be able to archive. Then again, when can you speak in absolutes about anything in life?

The point of archiving any of this material is ultimately for it to be used by future artists to better equip themselves to pick up where we have left off in the struggle against capitalist hegemony. The irony of using the tools of one current flavor of that hegemony (web technology, social media, surveillance/police-adjacent tech) is not lost. But accepting that this is our current social landscape and these are the tools and languages used by most people–including artists! who are just, like, regular people!–we can use the tools in ways that strengthen communities who need each others’ support in the material struggles against capitalism in all the local, specific practices they may manifest. And if capitalism takes us over the brink of climate collapse in the coming decades, we’ll need more powerful tools than ephemera archives I think to get back to cinema as a species.

Whew.

I also have to note that I’m writing this post in part as a mental escape from the horror of the school shooting today in Uvalde, Texas. It’s honestly impossible to comprehend how we keep returning to this same situation as a society, with half the people around us convinced that it’s fine and not something to fix at a systemic level. Or maybe we should just chuck the whole thing out rather than try to fix it. Let’s go back to the sea and leave the land to better creatures like beetles and nematodes.

References

Darr, Brian (May 19, 2022). “Gravity Spells Returns-‘Embrace the Vortex.’” Eat Drink Films, https://eatdrinkfilms.com/2022/05/20/gravity-spells-returns-embrace-the-vortex/

Hix, Lisa. (2010). “Oakland Art Gallery, Experimental Music Space, 21 Grand Set to Close,” KQED Arts, https://www.kqed.org/arts/38629/oakland_art_gallery_experimental_music_space_21_grand_set_to

Kashmere, Brett. (2014). “A subjective chronicle of microcinema exhibition,” Moving Image Review & Art Journal, volume 3(1), pp. 54-71.

White, Ted. (1997). “No Nothing Cinema” Found SF. https://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=NO_NOTHING_CINEMA